The Big Dipper is an asterism formed by seven bright stars in the northern circumpolar constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. It is one of the most recognizable star patterns in the night sky. The asterism is well-known in many cultures and goes by many different names, including the Plough, the Great Wagon, Charles’ Wain, Saptarishi, and the Saucepan.

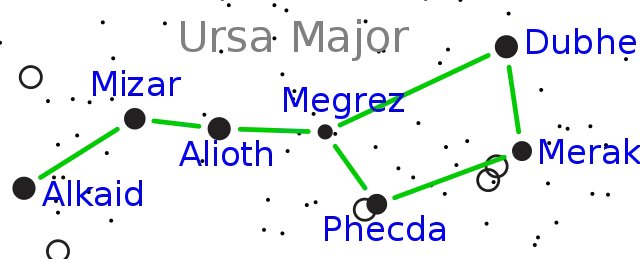

The seven stars that form the Big Dipper are: Alkaid (Eta Ursae Majoris), Mizar (Zeta Ursae Majoris), Alioth (Epsilon Ursae Majoris), Megrez (Delta Ursae Majoris), Phecda (Gamma Ursae Majoris), Dubhe (Alpha Ursae Majoris), and Merak (Beta Ursae Majoris). Six of these stars (all except Megrez) shine at second magnitude and can be spotted even from light-polluted areas.

In northern latitudes, the Big Dipper is visible throughout the year. It is one of the first star patterns we learn to identify, along with Orion’s Belt, Cassiopeia’s W, and the Northern Cross in the constellation Cygnus (the Swan).

Big Dipper (Ursa Major constellation) over Old Faithful geyser, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons/Astroval1 (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Constellation

The Big Dipper is the most visible part of the constellation Ursa Major, and its name is often used synonymously with the Great Bear. However, the Big Dipper itself is not a constellation. It is an asterism, a distinctive pattern formed by two or more stars. Its host constellation, Ursa Major, is the third largest constellation in the sky (after Hydra and Virgo) and covers a much larger area.

Ursa Major is one of the brightest northern constellations. With six second magnitude stars, it easily stands out in the sky even from urban areas.

The stars of the Big Dipper outline the Great Bear’s hindquarters and tail. The bowl of the Big Dipper corresponds to the Bear’s hindquarters and the curve of the Dipper’s handle to the Bear’s tail.

The rest of the constellation figure of Ursa Major is not as bright or as easy to see from light-polluted areas. Muscida (Omicron Ursae Majoris), the star that marks the Great Bear’s snout, appears almost halfway from Dubhe in the Big Dipper to Menkalinan in Auriga (the Charioteer).

The six stars that mark the Bear’s paws form an asterism called the Three Leaps of the Gazelle. They appear roughly halfway between the Bear’s head and the Big Dipper on one side and the constellation figure of Leo on the other. The fainter stars marking the Bear’s torso lie in the area between the Big Dipper’s bowl and Muscida, and those in the Bear’s thighs and legs between the Dipper’s bowl and the Three Leaps asterism.

The Big Dipper in winter, image credit: Giorgia Hofer/IAU OAE (CC BY 4.0)

Location

The Big Dipper and Ursa Major lie in the second quadrant of the northern hemisphere (NQ2). The entire constellation is visible from locations between the latitudes +90° and -30°. It is best seen in the evenings in April, when it makes its way across the sky during the night.

The Big Dipper is circumpolar in most of the northern hemisphere. This means that it never falls below the horizon and is visible throughout the year. As the Earth spins, the asterism appears to rotate slowly counterclockwise around the north celestial pole.

The bright star pattern is a more challenging target from the southern hemisphere. Dubhe, the northernmost star of the Big Dipper, lies at declination +61° 45′, which means that it never rises for observers north of the latitude 28° S. Even from southern locations where it does sometimes appear above the horizon, Dubhe stays very low in the sky.

Where is the Big Dipper?

For most observers, the Big Dipper always appears in the northern half of the sky. Depending on the time of year, it may be in the northeast, northwest or north in the evening. The asterism appears higher above the horizon from the far northern latitudes than it does from locations in the northern equatorial latitudes.

For northern observers, the asterism appears in the northeastern sky with the handle dangling from the bowl in the winter evenings. In the spring months, it is high in the northeast around 10 pm and travels across the sky during the night.

The location of the Big Dipper in different seasons, image: Stellarium

In the summer evenings, the Big Dipper is found above the northwestern horizon with the handle pointing upwards and the bowl closer to the horizon in the evening. In the autumn months, it lies low above the horizon in the northern sky.

Due to its location in the far northern sky, the Big Dipper is mostly invisible to observers in the southern hemisphere. It may be glimpsed from locations near the equator in the spring months, when it appears upside down above the northern horizon in the evening.

The Big Dipper as it appears from locations near the equator in the spring months, image: Stellarium

Constellations near the Big Dipper

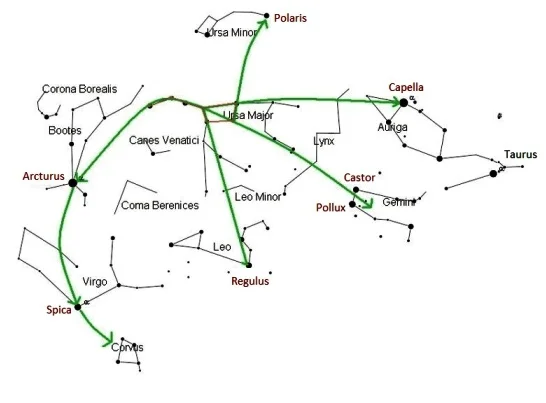

The Big Dipper can be used to find several neighbouring constellations, as well as a few that lie further away.

The arc of the Big Dipper’s handle points to Arcturus, the bear keeper, the brightest star in the constellation Boötes, the Herdsman. Boötes is recognizable for the asterism known as the Kite. Arcturus sits at the base of the Kite. It is the brightest star in the northern celestial hemisphere.

Following the line of the Big Dipper’s handle further leads to Spica, the brightest star in the constellation Virgo. Spica appears at the base of a crooked Y asterism that extends in the direction of Denebola in the constellation Leo. The Y of Virgo can be used to find the Virgo Cluster of galaxies.

Constellations near the Big Dipper, image: Stellarium

The region of the sky between the Big Dipper’s handle and the Y of Virgo is occupied by two fainter constellations. Coma Berenices, the home of the bright, large Coma Star Cluster, lies in the area between Arcturus and Denebola. The main constellation figure of Canes Venatici, the Hunting Dogs, is roughly parallel to the line connecting Alkaid and Mizar in the handle of the Big Dipper. Cor Caroli, the brightest star in Canes Venatici, is found below Alkaid, and the fainter Sun-like star Chara lies below Mizar.

The tail of Draco lies between the Big and Little Dippers. The rest of the celestial Dragon winds around the Little Dipper’s bowl in the direction of the Northern Cross in Cygnus.

The faint Lynx can be made out in good conditions between the head and front legs of the Bear, the heads of the celestial Twins (Pollux and Castor), and the hexagon of Auriga.

A line extended from Megrez through Phecda in the Big Dipper’s bowl leads to Regulus, the brightest star in Leo and the 21st brightest star in the sky. Leo is recognizable for the backward question mark pattern known as the Sickle. The asterism forms the celestial Lion’s head and mane, and Regulus appears at its base. The Lion’s tail is marked by Denebola. The line from Megrez though Phecda extended past Regulus leads to Alphard, the brightest star in Hydra.

The small, faint constellation Leo Minor lies between the constellation figure of Leo and the feet of the Great Bear. The Bear’s feet are marked by three pairs of stars between the Big Dipper and Leo. These stars form the old Arabic asterism called Three Leaps of the Gazelle.

The line of the Great Bear’s back (from Megrez to Dubhe) points toward Capella, the luminary of Auriga and the 6th brightest star in the sky. Castor in Gemini is found on the line drawn from Megrez through Merak and extended by about five times the distance as that between the two stars.

Big Dipper and the North Star

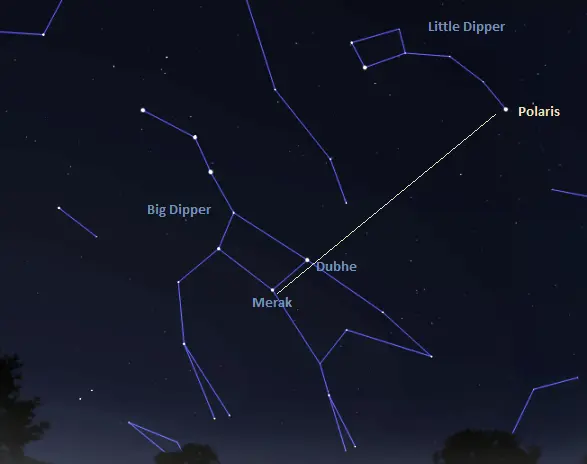

The stars of the Big Dipper can be used to find Polaris, the North Star. The two outer stars of the Big Dipper ’s bowl, Merak and Dubhe, are known as the Pointer Stars. A line extended from Merak through Dubhe points in the direction of Polaris.

Polaris lies in the constellation Ursa Minor, the Little Bear. It is the nearest visible star to the north celestial pole. The supergiant star is located less than a degree from the pole. The Big Dipper rotates around the pole and always points the way to the North Star.

Polaris is easily recognizable on a clear night because it is the brightest star in the Little Dipper asterism. It marks the end of the Little Dipper’s handle and the tip of the Little Bear’s tail.

Contrary to popular belief, Polaris is not exceptionally bright. It is the 48th brightest star in the sky. It stands out in the far northern sky because it appears in a region without any other bright stars. However, it is fainter than Alioth, Dubhe and Alkaid in the Big Dipper.

The Big Dipper and the North Star (Polaris), image: Stellarium

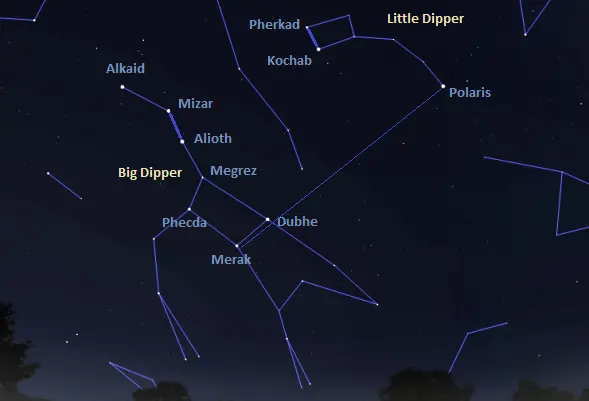

Big Dipper and Little Dipper

The Little Dipper is part of the constellation Ursa Minor (the Little Bear). It lies in the same area of the sky as the Big Dipper. It is formed by the seven brightest stars in Ursa Minor. However, its four middle stars are relatively faint and hard to see from urban areas. For this reason, the star pattern does not stand out in the sky and the bright stars of the Big Dipper are commonly used to find both the Little Dipper and true north.

Polaris lies along the imaginary line extended from the outer stars of the Big Dipper’s bowl (Merak and Dubhe). The stars Kochab and Pherkad, which form the outer part of the Little Dipper’s bowl, are quite bright and roughly parallel to the imaginary line connecting Mizar and Alioth in the Big Dipper’s handle. These stars are known as the Guardians of the Pole because they always circle around the North Star. The rest of the Little Dipper can be made out between Polaris and Kochab and Pherkad on a clear night.

The Big and Little Dippers, image: Stellarium

Big Dipper stars

The seven stars that make up the Big Dipper are:

- Alkaid (Eta Ursae Majoris)

- Mizar (Zeta Ursae Majoris)

- Alioth (Epsilon Ursae Majoris)

- Megrez (Delta Ursae Majoris)

- Phecda (Gamma Ursae Majoris)

- Dubhe (Alpha Ursae Majoris)

- Merak (Beta Ursae Majoris)

Alkaid, Mizar and Alioth form the Big Dipper’s handle and the Great Bear’s tail, while Megrez, Phecda, Dubhe and Merak outline the Dipper’s bowl and the Bear’s hindquarters.

Big Dipper stars, image: Luigi Chiesa (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Five of the seven Dipper stars belong to the Ursa Major Moving Group, also known as Collinder 285. The Ursa Major Moving Group (or Ursa Major association) is a group of stars that share a common proper motion and velocities in space. This indicates that they have the same origin and were formed in the same molecular cloud at about the same time. The white (class A) stars Mizar, Alioth, Megrez, Phecda and Merak are members of the group. The blue (B-type) main sequence star Alkaid and the orange giant Dubhe are not.

The stars of the Ursa Major association formed about 300 million years ago. The core of the group lies about 80 light years from Earth. Many bright stars outside of Ursa Major are also likely members, including Menkalinan in Auriga, Alphecca in Corona Borealis, Adhafera in Leo, and Skat in Aquarius.

The seven Big Dipper stars all have Arabic names. Most of their names refer to their position in the Great Bear. These names have been used for centuries. When the International Astronomical Union (IAU) set out to standardize star names in 2016, the traditional names of the seven stars were formally approved by the IAU’s Working Group on Star Names (WGSN).

The name Dubhe is derived from the Arabic żahr ad-dubb al-akbar, meaning “the back of the Greater Bear.” Merak comes from al-maraqq (the loins). Alioth is derived from the phrase alyat al-hamal (the sheep’s fat tail”). Phecda comes from fakhth al-dubb, “thigh of the bear,” and Megrez from al-maghriz, “the base (of the bear’s tail).”

The name Mizar means “covering” and comes from a mistaken reading of “loins.” It was drawn from the name of Mizar’s Big Dipper neighbour Merak.

The name Alkaid does not refer to the Great Bear. It is derived from the phrase qā’id bināt naʿsh, meaning “the leader of the daughters of the bier.” In ancient Arabic astronomy, the stars of the Big Dipper’s handle represented mourning maidens in a funeral procession, while the stars of the Big Dipper’s bowl represented the bier (coffin). The constellation’s slow circular movement around the pole was associated with the movement of a funeral procession. The stars of the handle represented the daughters of Al Na’ash, a man who met his end at the hands of Al Jadi, represented by the North Star (Polaris), the brightest star in the Little Dipper.

Alkaid

Alkaid, Eta Ursae Majoris (η UMa), is the star marking the end of the Big Dipper’s handle and the tip of the Great Bear’s tail. It is one of the hottest stars visible to the unaided eye. It is a very young star, with an estimated age of only 10 million years.

Alkaid is the third brightest star in Ursa Major and the 38th brightest star in the sky. It is a hot blue main sequence star of the spectral type B3V. It has an apparent magnitude of 1.86 and is about 103.9 light years distant from Earth.

Alkaid is 3.4 times larger, 6.1 times more massive and 594 times more luminous than the Sun. It has a surface temperature of about 15,540 K.

The name Alkaid means “the leader.” Eta Ursae Majoris was also traditionally known as Benetnasch.

The Big and Little Dippers in autumn, image credit: Giorgia Hofer/IAU OAE (CC BY 4.0)

Mizar

Mizar, Zeta Ursae Majoris (ζ UMa), is the middle star of the Big Dipper’s handle. It has an apparent magnitude of 2.23 and is 82.9 light years distant. It was the first double star to be photographed, in 1857.

Mizar is the fourth brightest star in Ursa Major and the 69th brightest star in the sky. It is the primary component of a multiple star system that consists of two spectroscopic binary stars. It forms a visual double star with the fainter Alcor, with which it may be physically associated. The two stars are sometimes known as the Horse and Rider.

Alcor itself has a fainter companion, so if it is indeed gravitationally bound to Mizar, this would make Zeta Ursae Majoris a six-star system. Both Mizar and Alcor are members of the Ursa Major Moving Group.

Mizar, the primary component in the Zeta UMa system, is a white main sequence star of the spectral type A2Vp. It has a mass 2.2224 times that of the Sun and a radius 2.4 times solar. With a surface temperature of about 9,000 K, it shines with 33.3 solar luminosities. The star is believed to be about 370 million years old.

The name Mizar comes from the Arabic miʼzar, meaning “covering.”

Alioth

Alioth, Epsilon Ursae Majoris (ε UMa), is the star in Ursa Major’s tail that is the closest to the bear’s body. It has a visual magnitude of 1.77 and is about 82.6 light years distant. It has the stellar classification of A1III-IVp kB9, indicating a white star that is coming to the end of its main sequence lifetime.

Alioth has a mass of 2.91 solar masses and a radius 4.29 times that of the Sun. It shines with 104.4 solar luminosities with an effective temperature of about 8,908 K. The star’s estimated age is 300 million years.

Alioth is a peculiar star, one that shows variations in its spectral lines over a period of 5.1 days. It is classified as an Alpha2 Canum Venaticorum variable. It is the brightest of the seven stars that form the Big Dipper asterism and the brightest star in the constellation Ursa Major.

The name Alioth comes from the Arabic phrase alyat al-hamal, meaning “the sheep’s fat tail.”

Megrez

Megrez, Delta Ursae Majoris (δ UMa), is the dimmest of the seven stars of the Big Dipper. It is the inner star of the Dipper’s bowl that is the closest to the tail. It has an apparent magnitude of 3.312 and lies at a distance of 80.5 light years.

Megrez is only the 11th brightest star in Ursa Major. It is outshone by other Big Dipper stars, as well as by Psi Ursae Majoris, Tania Australis (Mu UMa), Theta Ursae Majoris, and Talitha (Iota UMa) in the Great Bear’s legs and feet.

Megrez is a white main sequence star of the spectral type A3 V. It has a mass of 2.062 solar masses and a radius of 1.921 solar radii at the poles and 2.512 solar radii at the equator. It is believed to be around 414 million years old. The star is about 23 times more luminous than the Sun.

Mizar is a fast rotator. With a projected rotational velocity of 244.6 km/s, it takes only 3.1 hours to complete a rotation. As a result, it has an equatorial bulge and is flattened at the poles. Because the poles are closer to the star’s centre of mass, they are also hotter and more luminous than the equator. The star has an equatorial surface temperature of 6,909 K and a polar temperature of 10,030.

The name Megrez comes from the Arabic al-maghriz, meaning “the base.” It refers to the base of the Bear’s tail.

Little Dipper and Big Dipper in spring, image credit: Giorgia Hofer/IAU OAE (CC BY 4.0)

Phecda

Phecda, Gamma Ursae Majoris (γ UMa), has the stellar classification A0Ve, indicating another white main sequence dwarf. The star has a mass 2.412 times that of the Sun and an estimated age of 333 million years. It is 44.57 times more luminous than the Sun.

Like Mizar and Alkaid, Phecda is a fast spinner, and its poles are hotter than its equator. The star has an equatorial radius of 3.385 solar radii and a polar radius of 2.186 solar radii. It has an effective temperature of 10,520 K at the poles and 6,751 at the equator. Like many other fast spinning stars, Phecda is an Ae star and has emission lines in its spectrum. These lines indicate the presence of a gas envelope around the star.

Phecda has an astrometric binary companion, an orange dwarf of the spectral type K2 V. The companion regularly perturbs Phecda and causes it to wobble around the common centre of mass. The two stars have an orbital period of 20.5 years. The companion has a mass of 0.79 solar masses and is considerably cooler than the primary, with a surface temperature of 4,780 K. It shines with only 0.397 solar luminosities.

Phecda has an apparent magnitude of 2.438 and lies at a distance of 83.2 light years from Earth. It is the sixth brightest star in Ursa Major.

Gamma Ursae Majoris was traditionally also known as Phad. The names Phecda and Phad are derived from the Arabic fakhth al-dubb, meaning “thigh of the bear.”

Dubhe

Dubhe, Alpha Ursae Majoris (α UMa), has a visual magnitude of 1.79 and is about 123 light years distant from Earth. It is the second brightest star in Ursa Major, after Alioth.

Dubhe is an orange giant with the stellar classification of K0III. It is a spectroscopic binary star. It has a white main sequence companion of the spectral type A5V. The two stars are 23 astronomical units apart and have an orbital period of 44.45 years.

Dubhe is 3.7 times more massive than the Sun and 339 times more luminous. It is a slow spinner, with a projected rotational velocity of 2.63 km/s. The companion is less massive, with a mass of about 2.5 solar masses. It has a visual magnitude of 4.86.

The name Dubhe comes from the Arabic phrase żahr ad-dubb al-akbar, meaning “the back of the Greater Bear.”

Merak

Merak, Beta Ursae Majoris (β UMa), is a white subgiant star of the spectral type A1IVps. It has an apparent magnitude of 2.37 and is 79.7 light years distant. It is classified as a suspected variable.

The star has a mass of 2.56 solar masses and a radius 2.81 times that of the Sun. With a surface temperature of 9,700 K, it is 63.5 times more luminous than the Sun. The star’s estimated age is about 390 million years.

The name Merak comes from the Arabic al-marāqq, meaning “the loins.” It refers to the star’s position in the constellation Ursa Major.

Big Dipper facts

The brightest star in the Big Dipper asterism is Alioth, Epsilon Ursae Majoris. Alioth is the brightest star in Ursa Major and the 32nd brightest star in the sky. Dubhe (Alpha Ursae Majoris), the second brightest star, is only slightly fainter than Alioth. It is the 34th brightest star in the sky and one of the Pointer Stars (along with Merak), the stars used to find Polaris and the north celestial pole. Both Alioth and Dubhe are navigational stars. Their brightness and recognizability make them easy to use in the field of celestial navigation.

Even though it is the constellation’s brightest star, Alioth has the Bayer designation Epsilon Ursae Majoris. The German uranographer Johann Bayer, who introduced the system of stellar designations in his star atlas Uranometria (1603) that is still used today, assigned Greek letters to stars by order of magnitude, not by individual brightness. In the case of the Big Dipper and Ursa Major, Bayer assigned the letters going from west to east. This is why Dubhe, the westernmost of the constellation’s brightest stars, has the designation Alpha. Merak, the other Pointer Star, is Beta, and Alioth in the Dipper’s handle is Epsilon.

Five of the seven Big Dipper stars are part of the same family – the Ursa Major association – and they travel together through space. For this reason, the middle part of the asterism will not look significantly different even tens of thousands of years from now.

However, Alkaid and Dubhe do not belong to the Ursa Major association and have a different motion through space from the other Dipper stars. About 50,000 years from now, their motion will change the shape of the asterism. The handle will face the opposite way and the outer end of the bowl will appear slightly different.

The Big Dipper and Polaris are featured on the flag of Alaska. The Big Dipper’s host constellation, Ursa Major, represents a bear, an animal native to Alaska. The design of the flag was selected in a 1927 contest.

The Big Dipper, Orion’s Belt, the Northern Cross and Cassiopeia’s W are among the bright asterisms that make their host constellations instantly recognizable. Other prominent constellation-based patterns include the Teapot in the constellation Sagittarius (the Archer), the Fish Hook in Scorpius (the Scorpion), the Southern Cross in Crux, the Sickle of Leo in Leo (the Lion), Auriga’s hexagon in Auriga (the Charioteer), the Shaft of Aquila in Aquila (the Eagle), and the Golden Gate of the Ecliptic, formed by the Pleiades and Hyades open clusters in Taurus (the Bull).

Deep sky objects near the Big Dipper

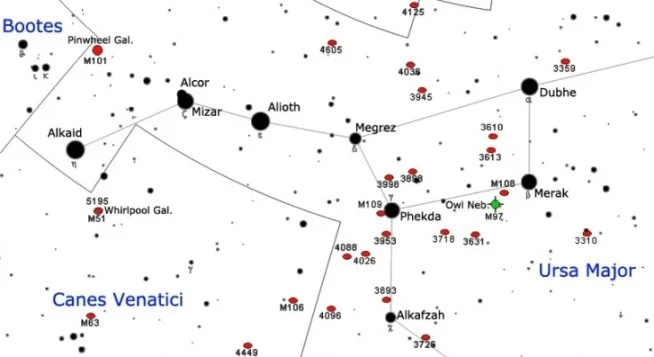

The Big Dipper lies in a region of the sky that hosts several bright deep sky objects. The Dipper stars can be used to find them. These objects lie in Ursa Major and in the neighbouring Canes Venatici.

The famous Whirlpool Galaxy (Messier 51) and the Sunflower Galaxy (Messier 63) can be found along the imaginary line connecting Alkaid in the Big Dipper’s handle and Cor Caroli in Canes Venatici. The Pinwheel Galaxy (Messier 101) appears above the Dipper’s handle and forms a triangle with Alkaid and Mizar.

Big Dipper map, image: Roberto Mura (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The galaxy pair Messier 81 and Messier 82 (Bode’s Galaxy and the Cigar Galaxy) can be found by extending a line from Phecda through Dubhe by about the same distance as that between the two stars. Bode’s Galaxy is one of the brightest spiral galaxies in the sky, along with the Andromeda Galaxy (NGC 224), the Triangulum Galaxy (NGC 598), and the Sculptor Galaxy (NGC 253).

A line drawn in the opposite direction, from Dubhe through Phecda toward Cor Caroli, leads to the spiral galaxy Messier 106.

Merak is the nearest bright star to the Owl Nebula (Messier 97) and the barred spiral galaxy Messier 108, and Phecda is less than a degree from the galaxy Messier 109.

Mythology

The Big Dipper is associated with many different myths and folk tales in cultures across the world. In Hindu astronomy, the asterism is called Saptarishi, or the Seven Great Sages. In eastern Asia, it is known as the Northern Dipper (Beidou in China, Hokuto Shichisei in Korea). The Chinese also know the seven stars as the Government, or Tseih Sing. In Malaysia, the asterism is called Buruj Biduk, or The Ladle, and in Mongolia, it is known as the Seven Gods.

In an old Arabic story, the stars that form the bowl represent a coffin and the three stars marking the handle are mourners following it. The name of the star Alkaid (or Benetnasch) refers to that story.

The association of Ursa Major with a bear has its origins in prehistoric times. Many civilizations have seen the celestial pattern as a bear. The best-known legend comes from Greek mythology. It links the constellation with the nymph Callisto, who was pursued by Zeus and transformed into a bear by his jealous wife Hera.

In the myth, Callisto had a son, Arcas, by Zeus. When Arcas grew up, he became a hunter and the king of Arcadia. During a hunt, he came across the bear and, not recognizing his mother, he aimed an arrow at it. However, Zeus intervened and turned the mother and son into the two bear constellations, Ursa Major and Ursa Minor.

Ursa Minor, the Little Bear, is a constellation of the northern hemisphere, and it contains the northern celestial pole, in our current epoch marked by a bright star called Polaris or the Pole Star. For centuries Polaris has been used for navigation in the northern hemisphere, as it has been almost at the exact pole position for roughly 200 years. In the Middle Ages and antiquity, there was no pole star; the celestial north pole lay in a dark region and the Greeks considered the “Little She-Bear” as a companion of the “Great She-Bear”, which is more easily recognizable. The brightest stars of these constellations were alternatively also considered as chariots by the Greeks, as written in Aratus’s famous didactic poem from the 3rd century before the common era. The most famous asterism in Ursa Major, composed of seven stars, has different names across the (northern) world. While considered as a chariot by the Greeks, it is “The Northern Dipper” in China, and “The Seven Oxen” for the ancient Romans. It was also the navigational purpose that led to the name The Great She-Bear, Ursa Major; for the Greeks, travelling towards the direction of the horizon above which Ursa Major appears meant moving towards the land of the bears (northern Europe). An animal is clearly recognizable when taking into account all the fainter stars in the vicinity of the seven bright ones. They considered it a female bear because Greek mythology connects this animal with the nymph Callisto, whose story describes the initiation rituals for women. During the year the relative positions of Ursa Minor and the Big Dipper don’t change, but all stars appear to be moved in a circle around Polaris. This star pointing due north lies at the point where Earth’s rotational axis intersects the celestial sphere. The shift of constellations throughout the year is a globe-clock or a globe-calendar, used by ancient civilizations to measure the year, and to predict the changes of seasons. It helps to establish, for instance, the best time for sowing and sailing as winds change with the seasons. Credit: Giorgia Hofer/IAU OAE (CC BY 4.0)

In the United Kingdom and Ireland, the Big Dipper asterism is known as the Plough, and sometimes as the Butcher’s Cleaver in northern parts of England. The old English name for the asterism is Charles’ Wain (wagon), which is derived from the Scandinavian Karlavagnen, Karlsvognen, or Karlsvogna. Charles or Karl was a common name in Germanic languages and the name of the asterism meant “the men’s wagon,” as opposed to the Little Dipper, which was “the women’s wagon.” An even older name for the stars of the Big Dipper was Odin’s Wain, or Odin’s Wagon, referring to Scandinavian mythology.

In Slavic languages and in Romanian, the Big and Little Dippers are known as the Great and Small Wagons. In German, the Big Dipper is known as Großer Wagen, the Great Cart. In Dutch, the asterism is popularly called Steelpannetje, the Saucepan, and in Finland it is called Otava (“salmon net”). The Italian name for the Big Dipper is Grande Carro (Great Wagon).

The Romans knew the seven stars as the “seven plough oxen,” or Septentrio, with only two of the seven stars representing oxen and the others forming a wagon pulled by the oxen.

The asterism was mentioned in Homer’s Iliad as “the Bear, which men also call the Wain.” In Homer’s time there was only one bear in the sky. The constellation Ursa Minor was introduced as a navigation aid at the suggestion of the Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus (c. 626/623 – 548/545 BCE). Greek sailors used Ursa Major for navigation and Thales imported the Little Bear from the Phoenicians around 600 BCE. Phoenician sailors used Kochab and Pherkad, the outer stars of the Little Dipper’s bowl, as markers of true north. At the time, the two bright stars were closer to the northern celestial pole than Polaris.

Some Native American groups saw the Dipper’s bowl as a bear and the three stars of the handle either as three cubs or three hunters following the bear. The second interpretation is linked to a folk tale that explains why leaves turn red in autumn: the hunters are chasing a wounded bear and, since the asterism is low in the sky at that time of year, the bear’s blood is falling on the leaves, making them turn red.

In more recent history, enslaved people in the United States knew the constellation as the Drinking Gourd and used it to find their way north, to freedom. The folk song, “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” gave the escaped slaves directions to follow the Big Dipper to get to north.

In Africa, the seven stars were sometimes seen as a drinking gourd, which is believed to be the origin of the name Big Dipper. The name is commonly used for the asterism in the United States and Canada.

Aurora borealis and the Big Dipper glowing over Chisasibi, Quebec, Canada. Image credit: Carl Young (CC BY-SA 4.0)