Deep in the northern constellation Cepheus, near the north celestial pole, lies one of astronomy’s most intriguing objects. The Valentine Rose Nebula – formally catalogued as Sharpless 2-174 (Sh2-174) – appears as a delicate, asymmetric bloom of glowing ionized gas in long-exposure photographs.

The asymmetric structure of this faint emission nebula hints at a complex history. For decades, astronomers classified this unusual object as an ancient planetary nebula, the final breath of a Sun-like star. However, as observational technology improved and new data emerged, that interpretation began to unravel.

Today, Sh2-174 stands at the centre of an ongoing debate about stellar evolution and the nature of ionized gas clouds. Is it truly a planetary nebula—the expanding shell cast off by a low-mass star at the end of its life? Or is it something more mundane: ambient interstellar gas being illuminated by a passing white dwarf? The answer reveals fundamental insights about how we classify astronomical objects and how those classifications evolve as our understanding deepens.

This image of Sharpless 2-174 was obtained with the wide-field view of the Mosaic camera on the Mayall 4-meter telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory. It was generated with observations in the B (blue), I (orange), Hydrogen-alpha (red) and Oxygen [OIII] (blue) filters. In this image, North is up, East is to the left. Image credit: T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage) and H. Schweiker (WIYN and NOIRLab/NSF/AURA) (CC BY 4.0)

From Photographic Plates to Scientific Puzzle

Sh2-174 was first catalogued in 1959 by the American astronomer Stewart Sharpless in his landmark Catalogue of H II Regions. Using photographic plates from the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS), he identified it as a faint emission nebula roughly 10 arcminutes across. At the time, little more was known than that it emitted hydrogen-alpha radiation – a signature of ionized gas.

In 1965, American astronomer Beverly Turner Lynds included the object in her Catalogue of Bright Nebulae as LBN 120.29+18.39 (also referred to as LBN 598).

The turning point came in 1970, when Giclas and colleagues identified a hot white dwarf – GD 561 – projected in the same line of sight. This discovery would reshape interpretations of Sh2-174 for the next two decades.

The Classic Explanation: A Fading Planetary Nebula

The presence of a hot white dwarf near Sh2-174 suggested an obvious explanation. Planetary nebulae form when low- to intermediate-mass stars exhaust their nuclear fuel and shed their outer layers into space. The exposed core – destined to become a white dwarf – emits intense ultraviolet radiation that ionizes the expelled gas, causing it to glow. Over thousands of years, this material disperses into the interstellar medium (ISM) while the central star continues cooling.

The Valentine Rose Nebula fit this profile remarkably well. It appeared as a diffuse, roughly circular emission nebula with GD 561 positioned nearby. Its large size and faint structure suggested an advanced evolutionary stage – a nebula thousands of years into its expansion and dispersal. In 1984, Fich and Blitz determined a distance of approximately 718 light-years (220 parsecs), yielding a physical radius of about 0.98 light-years (0.3 parsecs) for the nebula, consistent with known planetary nebulae.

The interpretation solidified in 1993 when Napiwotzki and Schönberner compared spectrograms of GD 561 with the central stars of the planetary nebulae Sharpless 2-216 in the constellation Perseus and the Helix Nebula (NGC 7293) in Aquarius. The striking similarities confirmed that the Valentine Rose exhibited the spectroscopic signatures expected of a planetary nebula. Even the prominent [OIII] emission lines – typical markers of ionized oxygen in planetary nebulae – were clearly visible.

Astronomers explained the nebula’s asymmetry by invoking interaction with the interstellar medium. As planetary nebulae expand and move through space, pressure from surrounding gas can distort their originally symmetric shells. Sh2-174 appeared compressed on one side and diffuse on the other—exactly what models predicted for an old planetary nebula ploughing through denser regions of the galaxy. The object seemed to represent one of the more evolved examples of this planetary nebula-ISM interaction process.

For years, the case seemed closed. Astronomers accepted that the nebula lay at the centre of a large cloud of neutral hydrogen about 1.2 by 0.4 degrees in size and that it did not share the same origin with the cloud. A 2015 study of the central star’s space velocity showed that the star and the planetary nebula entered the cloud approximately 27,000 years ago.

Cracks in the Story: New Data Raises Doubts

As spectroscopy and kinematic measurements improved in the 1990s and 2000s, inconsistencies emerged.

Detailed spectroscopic studies revealed that the gas in Sh2-174 didn’t behave quite like typical planetary nebula material. Measurements of density, velocity structure, and emission-line ratios suggested that the gas more closely resembled diffuse interstellar hydrogen rather than stellar ejecta.

In classical planetary nebulae, gas expands outward from a central star at measurable velocities. Sh2-174 instead looked relatively static, more like interstellar gas than expelled material. Studies of radial velocities suggested that GD 561 and the surrounding nebula might not share the evolutionary connection required by the planetary nebula model.

The nebula’s structure also raised questions. Sh2-174 lies in a relatively dense region of the interstellar medium, and its morphology aligns better with models of a white dwarf moving through ambient gas than with a star dispersing its own expelled envelope.

The Alternative: An H II Region in Disguise

An alternative explanation gained traction: the Valentine Rose might not be a planetary nebula at all, but rather an ionized H II region created by GD 561 as it travels through pre-existing interstellar material. In this scenario, the gas never belonged to the white dwarf. Instead, GD 561 – still hot enough to emit substantial ultraviolet radiation – ionizes the hydrogen in its path, creating a glowing wake through the ambient medium.

White dwarfs can exceed surface temperatures of 100,000 Kelvin early in their cooling history, producing enough ionizing photons to light up nearby gas. If GD 561 is moving through a dense interstellar cloud at significant velocity – estimates suggest around 71 km/s relative to the local medium – it would naturally create an ionized region with an asymmetric, disrupted appearance.

This interpretation explains several puzzling features. The offset position of GD 561, once thought to result from the star drifting from the centre of the nebula over time, instead reflects the star’s motion through stationary gas. The asymmetry arises not from ISM interaction distorting an expanding shell, but from the directional motion of the ionizing source itself. The velocity measurements, previously problematic for the planetary nebula model, make perfect sense if the gas is ambient material rather than co-moving ejecta.

Current estimates place the Valentine Rose Nebula at an approximate distance of 980 – 1,000 light-years (300 parsecs), though some sources suggest distances as great as 1,800 light-years depending on the measurement technique used. These revised distances affect calculations of the nebula’s physical size and the energy budget required to ionize it, but they remain consistent with the H II region model.

GD 561: Central Star or Cosmic Wanderer?

The white dwarf GD 561 sits at the heart of this debate. Spectroscopic analysis by Bergeron and colleagues in 1992 assigned it the spectral type DAO, indicating a hot white dwarf with both hydrogen and helium lines in its spectrum. The star’s surface temperature has been estimated at approximately 65,000 Kelvin – hot enough to ionize the surrounding hydrogen.

Under the planetary nebula model, GD 561 would be the direct evolutionary successor of the star that expelled Sh2-174’s gas. Its high temperature and spectroscopic properties would result from recent emergence from the asymptotic giant branch phase. The long cooling timescale of white dwarfs means GD 561 could maintain ionizing temperatures for hundreds of thousands of years after shedding its envelope.

Under the H II region model, GD 561 is instead an unrelated white dwarf passing through a pre-existing interstellar cloud. Its radiation ionizes the surrounding hydrogen without requiring the gas to have originated from the star itself. This distinction is subtle but profound: in one case, we observe stellar debris; in the other, we witness stellar illumination.

Interestingly, Tweedy and Napiwotzki’s 1994 study proposed that GD 561 might be part of a close binary system, a low-mass helium white dwarf formed through envelope stripping after core hydrogen burning. If true, this would explain apparent inconsistencies in the star’s evolutionary timescales and raise further questions about its connection to the surrounding nebula.

Lessons from Uncertainty

The Valentine Rose Nebula stands as a reminder that astronomy is a science of continuous refinement. Objects once confidently classified can require rethinking as observations improve and models evolve. What seemed like a straightforward case of a planetary nebula interacting with its environment revealed complications that challenged the entire interpretation.

The evolving observations of Sh2-174 illustrate how astronomical classifications shift as technology and understanding advance. In the 1950s, it was simply an emission nebula. By the 1990s, it had become a textbook example of an evolved planetary nebula interacting with the interstellar medium. Today, many researchers favour the H II region interpretation, though uncertainty remains.

This progression reflects a broader lesson in astronomy: morphology alone is not enough. Early observations emphasized the nebula’s shape and its proximity to a white dwarf. Later studies added kinematic data, emission-line diagnostics, and improved distance estimates, gradually shifting the balance of evidence. Each new measurement refined our understanding, revealing complexities invisible in earlier work.

How to Find the Valentine Rose

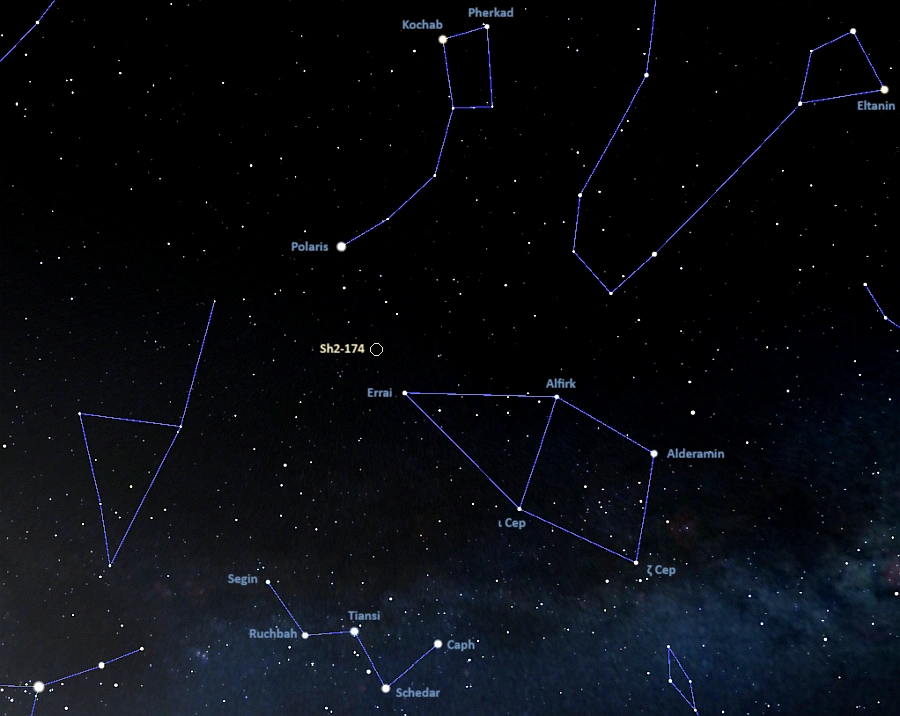

The nebula Sh2-174 lies in the far northern sky, in the region of the northern celestial pole. It appears in the same area as the Polarissima Cluster (NGC 188). It can be found less than a third of the way from Errai (Gamma Cephei) to Polaris (Alpha Ursae Minoris).

Polaris, the North Star, lies along the imaginary line extended from Merak through Dubhe, the outer stars of the Big Dipper’s bowl. Errai marks the top of the roof in the stick house asterism that dominates the constellation Cepheus.

Location of Sharpless 2-174 (the Valentine Rose Nebula), image: Stellarium (annotated for this website)

Sh2-174 ranks among the most challenging objects in the Sharpless catalogue for amateur observers. With an apparent magnitude of 14.74, it lies far below the limit of binoculars and small telescopes. Even large amateur instruments struggle to reveal more than a faint glow under excellent conditions. The nebula’s diffuse structure and low surface brightness demand long-exposure imaging with narrowband filters—particularly hydrogen-alpha and [OIII]—to bring out its delicate morphology.

The best time of the year to observe the Valentine Rose Nebula and other deep sky objects in Cepheus is during the month of November, when the constellation appears higher above the horizon in the early evening. However, as one of the northernmost constellations in the sky, the celestial King is circumpolar from the northern hemisphere and can be seen year-round.

Valentine Rose Nebula – Sharpless 2-174

| Constellation | Cepheus |

| Object type | HII region |

| Right ascension | 23h 45m 02.268s |

| Declination | +80° 56′ 59.62″ |

| Apparent magnitude | 14.74 |

| Apparent size | 20′ |

| Distance | 978 light years (300 pc) |

| Names and designations | Valentine Rose Nebula, Sharpless 2-174, Sh2-174, LBN 598, LBN 120.29+18.39, PN G120.3+18.3, PK 120+18 1, GSC2 N0100201660 |