On the night of February 24, 1987, astronomers witnessed something extraordinary: a brilliant supernova visible from Earth without a telescope for the first time in nearly four centuries. Known as Supernova 1987A, the stellar event sent shockwaves—not just through space, but through the scientific community. More than a spectacular cosmic sight, SN 1987A became a once-in-a-generation opportunity to study how stars end their lives, offering insights that continue to shape our understanding of the universe decades later.

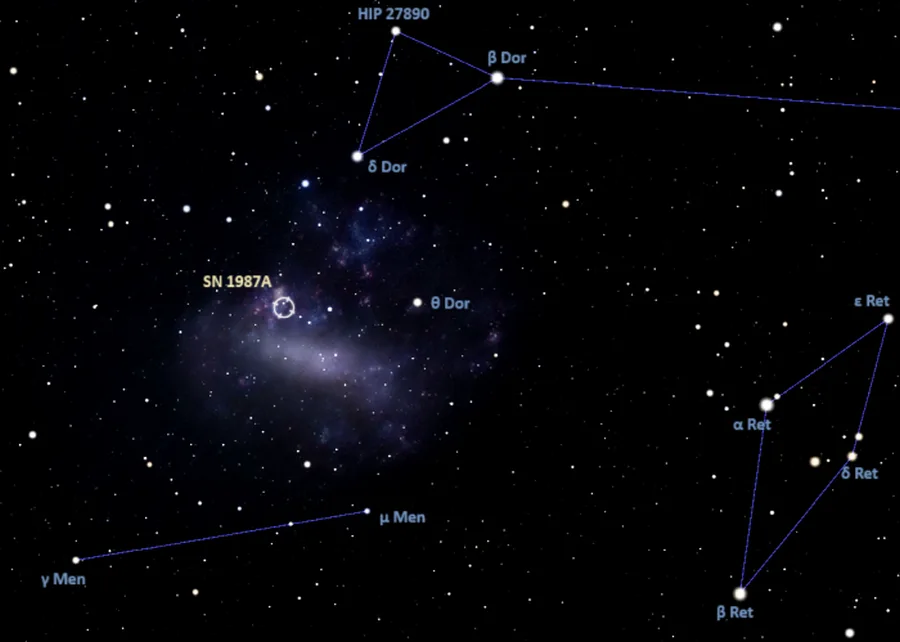

Supernova 1987A (SN 1987A) is the remnant of a type II supernova observed in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) in the constellation Dorado in 1987. It occurred at a distance of 168,000 light-years from the Sun. Its light first reached Earth on February 23, 1987, and was discovered a day later. The progenitor star was a blue supergiant catalogued as Sanduleak −69 202.

At its peak, SN 1987A shone at magnitude 2.7 and was easily visible to the unaided eye. It appeared brighter than Dorado’s brightest star, the massive binary system Alpha Doradus (mag. 3.236 – 3.276). It was designated SN 1987A because it was the first supernova detected in 1987.

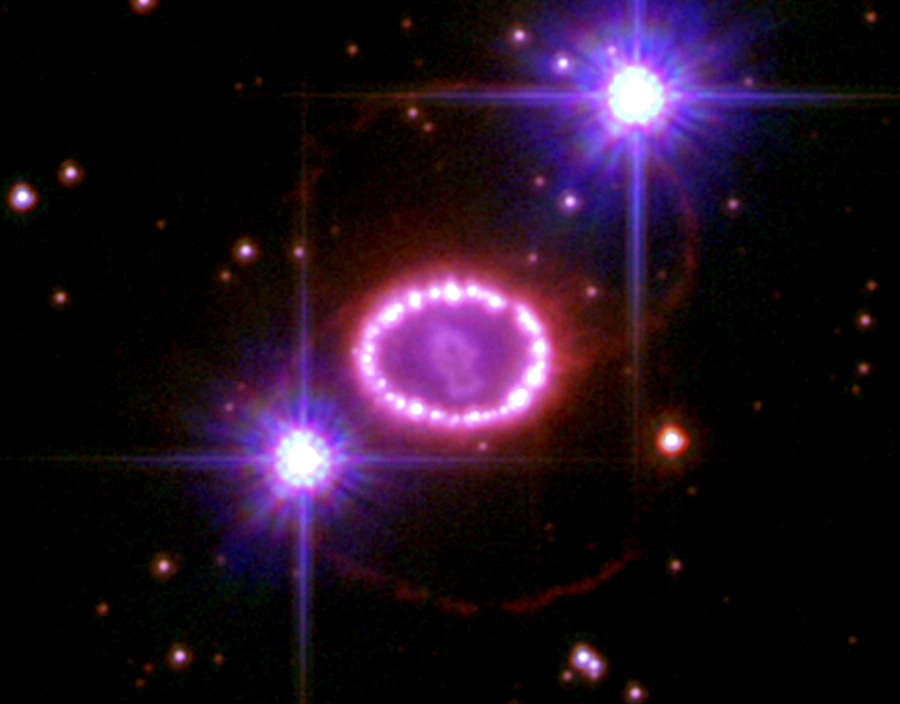

In the 1980s, astronomers witnessed one of the brightest supernovae in more than 400 years. The titanic supernova, called SN 1987A, blazed with the power of 100 million suns for several months following its discovery on Feb. 23, 1987. Observations of SN 1987A, made by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and many other major ground- and space-based telescopes, have significantly changed astronomers’ views of how massive stars end their lives. Astronomers credit Hubble’s sharp vision with yielding important clues about the massive star’s demise. This Hubble telescope image shows the supernova’s triple-ring system, including the bright spots along the inner ring of gas surrounding the progenitor star. A shock wave of material unleashed by the powerful event is slamming into regions along the inner ring, heating them up, and causing them to glow. The ring, about a light-year across, was probably shed by the star about 20,000 years before it went out as a supernova. Image credit: NASA, ESA, P. Challis, and R. Kirshner (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) (PD)

The dramatic end of the massive star was mainly visible from the southern hemisphere. At declination -69°, it could not be seen from locations north of the latitude 21° N. It was the first visible supernova since the invention of the telescope and the closest observed supernova since Kepler’s Supernova (SN 1604).

Because of its proximity, SN 1987A is one of the most studied supernova remnants in the sky. It has provided astronomers with a new understanding of the early stages in the evolution of supernova remnants, as well as the late stages in the life cycle of blue supergiant stars.

How Supernova 1987A changed our understanding of stellar evolution

The Supernova 1987A played a huge role in advancing supernova physics. For the first time, astrophysicists had an opportunity to study not only the supernova itself and the evolving remnant, but also its progenitor star.

Deep imaging of the remnant revealed a system of three glowing rings of gas, which helped trace the mass loss history of the progenitor star tens of thousands of years before the supernova event. The insights helped astronomers refine their models of how massive stars shed material before they go out.

Observations of SN 1987A led to several key discoveries that marked a big leap forward for theoretical models of core-collapse supernovae. They provided the first evidence that blue supergiants could be supernova progenitors, which led to major revisions of stellar evolution models.

Additionally, they gave astronomers the first direct glimpse of supernova neutrinos, effectively marking the birth of neutrino astronomy.

In the decades that followed the discovery of the supernova, the remnant was observed by the most powerful telescopes, including the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA), and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Even though SN 1987A was one of the most extensively studied supernova remnants in the sky, observations did not reveal any evidence of a black hole or neutron star left in the supernova’s wake until 2019.

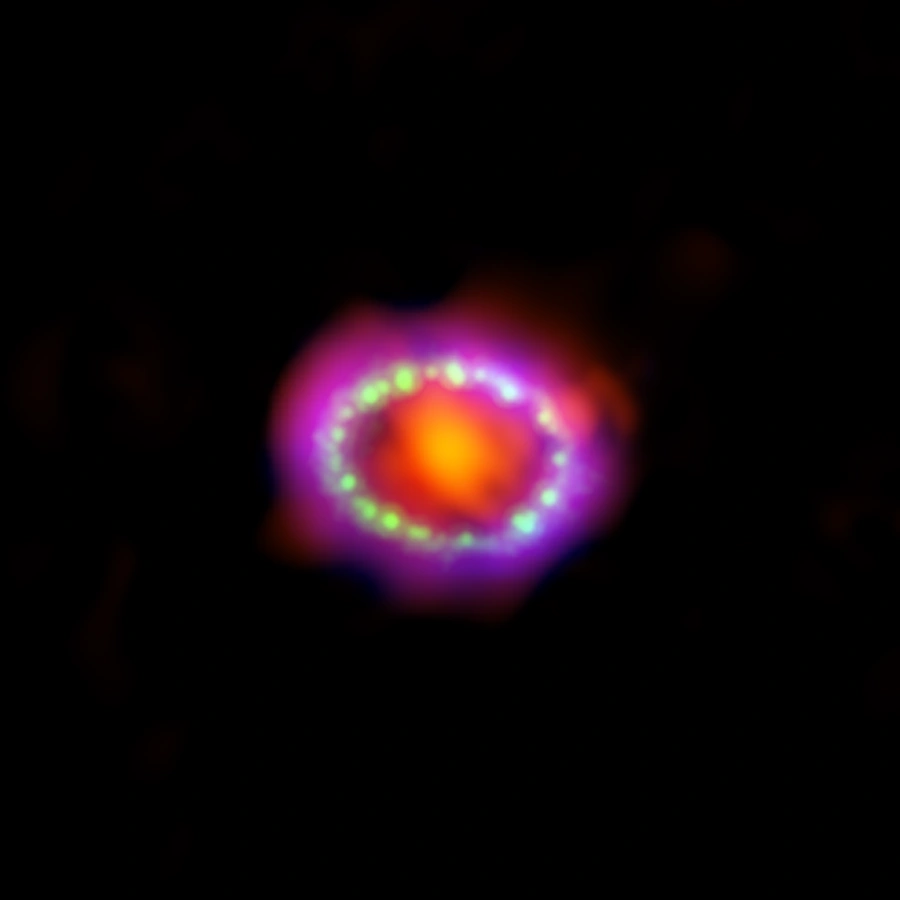

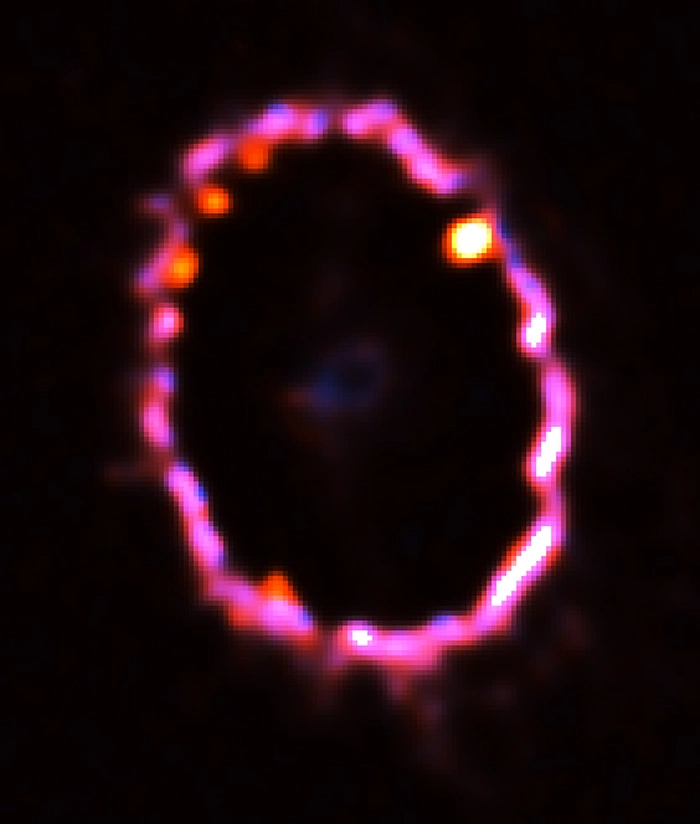

With its superb sensitivity at millimetre and submillimetre wavelengths, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) has been exploring previously unstudied aspects of SN 1987A since 2013. Astronomers are using ALMA to observe the glowing remains of the supernova in high resolution, studying how the remnant is making vast amounts of dust from the new elements created in the progenitor star. A portion of this dust will make its way into interstellar space and may one day be the material from which future planets around other stars are made. These observations suggest that dust in the early Universe was created by similar supernova events. The composite image presented here combines observations made with ALMA, the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and NASA’s Chandra X-Ray observatory. Credit – ALMA: ESO/NAOJ/NRAO/A. Angelich; Hubble: NASA, ESA, R. Kirshner (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation) and P. Challis (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics); Chandra: NASA/CXC/Penn State/K. Frank et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Blue supergiants as supernova progenitors

Observations of the Supernova 1987A provided the first direct confirmation that blue supergiants were natural supernova progenitors, which was initially surprising to astronomers. At the time, there was growing evidence that all massive stars showed enhanced nitrogen abundances prior to going out as supernovae. However, these stars were not definitively proven to be supernova progenitors before SN 1987A.

The blue supergiant Sanduleak −69 202 (Sk -69 202) was identified as the progenitor four days after the detection of SN 1987A. Observations with the International Ultraviolet Explorer (IUE) showed that the star that coincided with the location of the supernova had disappeared from sight when the supernova occurred.

The supergiant had the spectral type B3 Ia. Astronomers found that it was a post-red supergiant that was evolving blueward in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, and that it had a nitrogen-rich circumstellar shell of material. The shell was likely expelled from the star during the red supergiant stage.

Sanduleak −69 202 was located on the outskirts of the Tarantula Nebula (30 Doradus), a vast H II region in the Large Magellanic Cloud. The massive star was first catalogued by the Romanian-American astronomer Nicholas Sanduleak in 1970. It had an estimated mass of 20 solar masses and shone with around 100,000 solar luminosities.

A 2006 study proposed that Sk -69 202 was in fact a luminous blue variable (LBV). The supergiant star was surrounded by a nebula almost identical to those found around the blue supergiants and LBV candidates Sher 25 near the giant starburst region NGC 3603 in the constellation Carina and HD 168625 (V4030 Sagittarii) near the Omega Nebula (M17) in Sagittarius. This has led astronomers to believe that the two stars are likely to go out as supernovae in the relatively near future.

Luminous blue variables are a group of exceptionally rare, evolved massive stars that show sudden dramatic variations in brightness caused by giant outbursts. The most famous of these stars, Eta Carinae A, has an estimated mass of 100 solar masses and a luminosity of 4 million Suns. Other well-known examples include S Doradus in the constellation Dorado, P Cygni in Cygnus, Zeta1 Scorpii and Wray-17-96 in Scorpius, and AG Carinae in Carina.

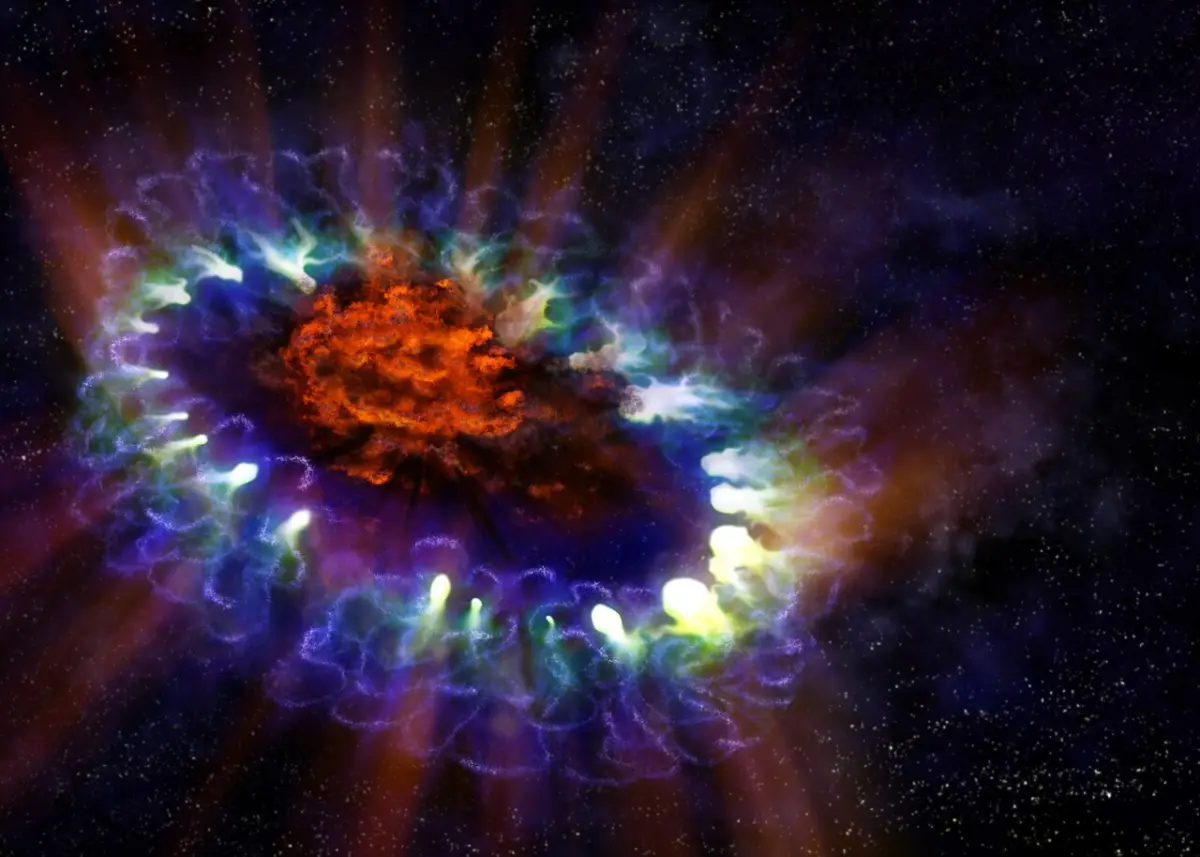

This artist’s illustration of Supernova 1987A is based on real data and reveals the cold, inner regions of the star’s remnants (in red) where tremendous amounts of dust were detected and imaged by ALMA. This inner region is contrasted with the outer ring (lacy white and blue circles), where the shock wave from the supernova is colliding with the envelope of gas ejected from the star prior to the supernova event. This ring was initially lit up by the ultraviolet flash from the original event, but over the past few years the ring material has brightened considerably as it collides with the expanding shockwave. Image: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/Alexandra Angelich (NRAO/AUI/NSF) (CC BY 4.0)

First detection of neutrinos from a supernova

Several hours before Supernova 1987A became visible from Earth, three neutrino observatories reported the detection of a flash of neutrinos. Neutrinos are neutral, virtually massless elementary particles that are produced during certain high-energy events. These particles travel at velocities close to the speed of light, passing through matter without scattering and maintaining a straight path.

Supernova neutrinos are produced during core-collapse supernovae. They carry away virtually all the progenitor star’s gravitational energy. The neutrino bursts associated with supernovae last only tens of seconds. SN 1987A provided astronomers with the first ever opportunity to observe neutrinos emitted by a supernova directly.

The KamioKANDE proton decay detector at the Kamioka Observatory in Japan detected the neutrinos as they arrived in two pulses. The first pulse arrived on February 23 at 7:35:35. It comprised nine neutrinos and lasted only 1.915 seconds. The second pulse comprised three neutrinos that arrived within 3.220 seconds about 10 seconds after the first pulse.

The discovery of neutrinos confirmed theoretical models of core-collapse supernovae, demonstrating that around 99 percent of the collapsing star’s energy is released as these particles.

Recent Chandra observations have revealed new details about the fiery ring surrounding the remnant of the Supernova 1987A. The data give insight into the behavior of the doomed star in the years before it went out, and indicate that the predicted spectacular brightening of the circumstellar ring has begun. Previous optical, ultraviolet and X-ray observations have enabled astronomers to piece together the following scenario for the progenitor (SK -69): about ten million years ago the star formed out of a dark, dense, cloud of dust and gas; roughly a million years ago, it lost most of its outer layers in a slowly moving stellar wind that formed a vast cloud of gas around it; before the star went out, a high-speed wind blowing off its hot surface carved out a cavity in the cool gas cloud. The intense flash of ultraviolet light from the supernova illuminated the edge of this cavity to produce the bright ring seen by the Hubble Space Telescope. In the meantime the supernova sent a shock wave rumbling through the cavity. In 1999, Chandra imaged this shock wave, and astronomers have waited expectantly for the shock wave to hit the edge of the cavity, where it would encounter the much denser gas deposited by the red supergiant wind, and produce a dramatic increase in X-radiation. The latest data from Chandra and the Hubble Space Telescope indicate that this much-anticipated event has begun. Optical hot-spots now encircle the ring like a necklace of incandescent diamonds. The Chandra image reveals multimillion-degree gas at the location of the optical hot-spots. X-ray spectra obtained with Chandra provide evidence that the optical hot-spots and the X-ray producing gas are due to a collision of the outward-moving supernova shock wave with dense fingers of cool gas protruding inward from the circumstellar ring. These fingers were produced long ago by the interaction of the high-speed wind with the dense circumstellar cloud. The dense fingers and the visible circumstellar ring represent only the inner edge of a much greater, unknown amount of matter ejected long ago by SK -69. As the shock wave moves into the dense cloud, ultraviolet and X-radiation from the shock wave will heat much more of the circumstellar gas. Then, as remarked by Richard McCray, one of the scientists involved in the Chandra research, “Supernova 1987A will be illuminating its own past.” Image credit – X-ray: NASA/CXC/PSU/S.Park & D.Burrows.; Optical: NASA/STScI/CfA/P.Challis (PD)

Expanding rings and shockwaves around Supernova 1987A

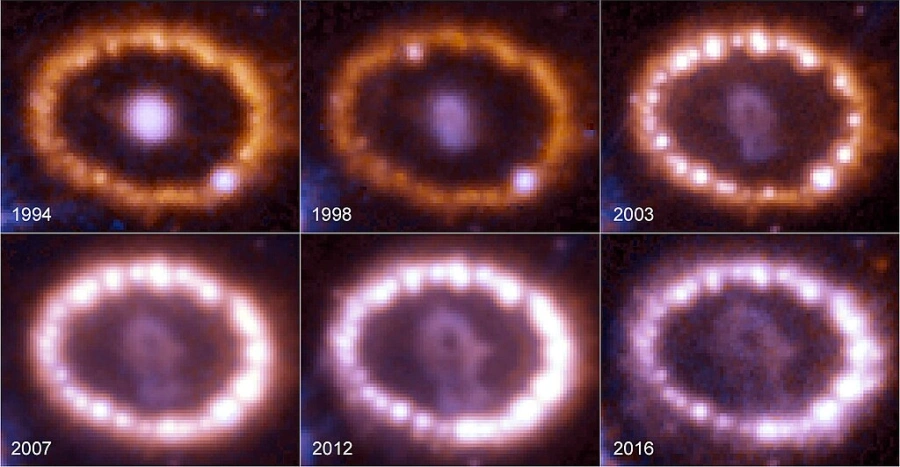

A few months after the discovery of SN 1987A, Hubble captured three bright rings around the glowing remains of the supernova. These rings are composed of material expelled by the progenitor in an earlier evolutionary stage through a strong stellar wind. As they were ionized by the flash of ultraviolet light from the supernova event, the rings started to glow.

The inner ring has a radius of 0.808 arcseconds. Between 2001 and 2009, the X-ray emission from the ring increased significantly. The increase in X-ray flux was caused by the collision of the supernova ejecta with the ring of previously expelled material, which occurred around 2001. Astronomers have predicted that the ring would fade between 2020 and 2030.

The supernova shock wave moved past the ring by 2018. As it moved through the stellar debris, the shock wave has revealed details of the evolution of the star that produced the supernova. It has provided scientists with new insights into the life of the pre-supernova star, especially the mass loss in the late stages of its life.

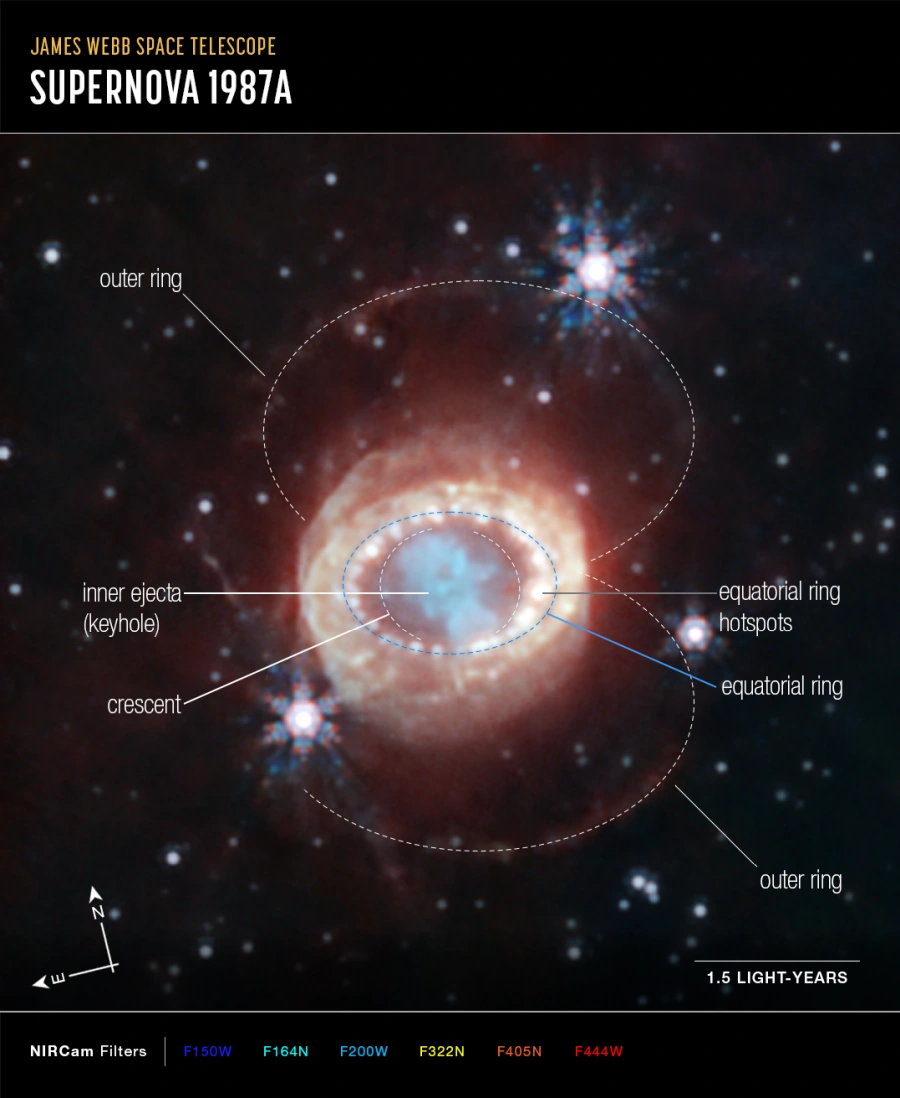

The NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope has begun the study of one of the most renowned supernovae, SN 1987A (Supernova 1987A). Located 168,000 light-years away in the Large Magellanic Cloud, SN 1987A has been a target of intense observations at wavelengths ranging from gamma rays to radio for nearly 40 years, since its discovery in February of 1987. New observations by Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) provide a crucial clue to our understanding of how a supernova develops over time to shape its remnant. This image reveals a central structure like a keyhole. This center is packed with clumpy gas and dust ejected by the supernova event. The dust is so dense that even near-infrared light that Webb detects can’t penetrate it, shaping the dark “hole” in the keyhole. A bright, equatorial ring surrounds the inner keyhole, forming a band around the waist that connects two faint arms of hourglass-shaped outer rings. The equatorial ring, formed from material ejected tens of thousands of years before the supernova, contains bright hot spots, which appeared as the supernova’s shock wave hit the ring. Now spots are found even exterior to the ring, with diffuse emission surrounding it. These are the locations of supernova shocks hitting more exterior material. Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, M. Matsuura (Cardiff University), R. Arendt (NASA’s Goddard Spaceflight Center & University of Maryland, Baltimore County), C. Fransson (Stockholm University), J. Larsson (KTH Royal Institute of Technology), A. Pagan (STScI) (CC BY 4.0)

Search for the stellar remnant

Type II supernovae are triggered by the rapid core collapse of a massive star when the star reaches the end of its evolutionary cycle. Depending on the progenitor star’s mass, these supernovae produce either neutron stars or black holes.

Stars like Sanduleak -69 202 leave behind neutron stars when they go out. A neutron star is the gravitationally collapsed core of a supergiant star. It is an exceptionally dense, compact object.

These compressed cores are the second smallest and densest stellar objects known, after black holes. They typically pack a mass of 1.4 solar masses into a radius of only 10 kilometers (6 miles).

Even though the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) has captured images of the region around SN 1987A regularly since it began operations in 1990, astronomers were unable to detect the progenitor star’s collapsed core for several decades.

The first evidence for the neutron star was presented in 2019, more than 30 years after the supernova event. A team of astronomers led by Phil Cigan, School of Physics and Astronomy, Cardiff University, UK, studied data obtained with the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA). They proposed that the stellar remnant may be located within one of the brightest dust clumps in the remnant. The study was published in The Astrophysical Journal.

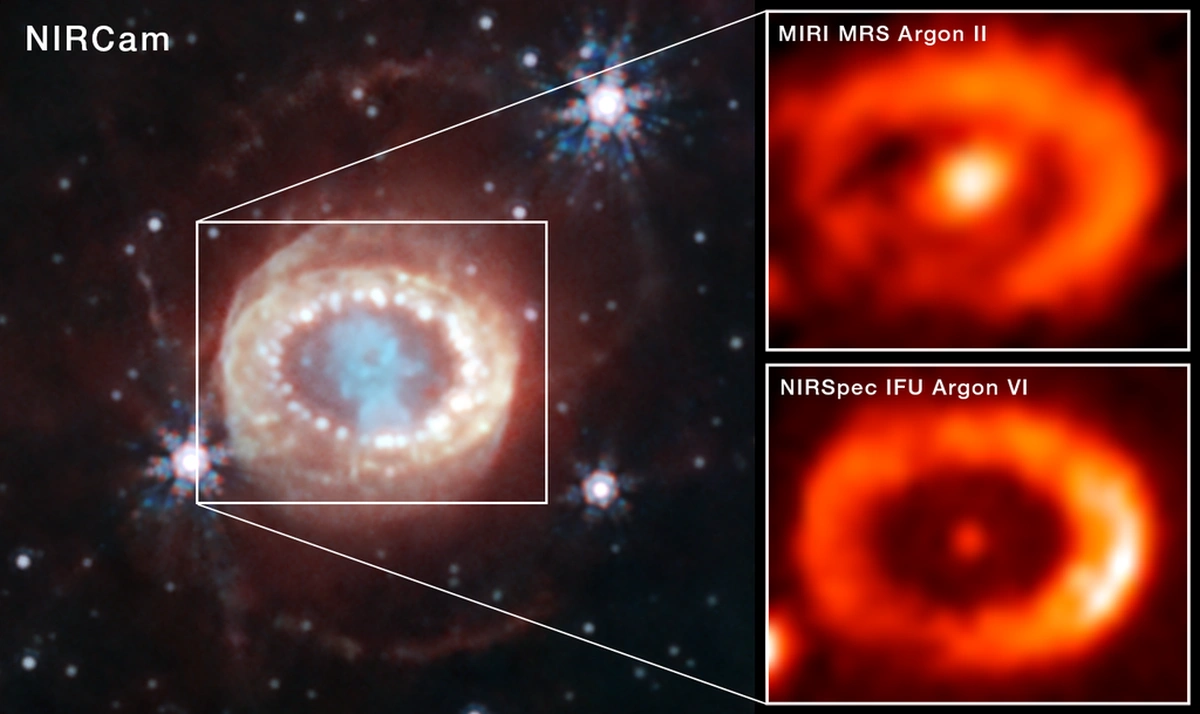

The James Webb Space Telescope has observed the best evidence yet for emission from a neutron star at the site of a well-known and recently-observed supernova known as SN 1987A. At left is a NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) image released in 2023. The image at top right shows light from singly ionized argon (Argon II) captured by the Medium Resolution Spectrograph (MRS) mode of MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument). The image at bottom right shows light from multiply ionized argon captured by the NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph). Both instruments show a strong signal from the center of the supernova remnant. This indicated to the science team that there is a source of high-energy radiation there, most likely a neutron star. Image: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Claes Fransson (Stockholm University), Mikako Matsuura (Cardiff University), M. Barlow (UCL), Patrick Kavanagh (Maynooth University), Josefin Larsson (KTH) (PD)

In 2024, observations with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) allowed researchers to identify narrow infrared emission lines of argon and sulfur. These lines were interpreted as gas illuminated by an ionizing source near the centre of the expanding ejecta. Astronomers found that the lines indicated ionization by a central cooling neutron star or a pulsar wind nebula.

The stellar remnant was previously difficult to detect because it was wrapped in a cocoon of thick dust and ejecta that formed in the inner regions after the supernova event.

Unless they emit strong radio pulses like the Crab Pulsar in the Crab Nebula (M1), neutron stars are not strong enough emitters to stand out from the turbulent environment around them. Any output would be lost in the intense X-ray and radio emission produced by the interaction of the supernova shock wave with the circumstellar rings of material.

This montage shows the evolution of the supernova 1987A between 1994 and 2016, as seen by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. The supernova was first spotted in 1987 and is among the brightest supernovae within the last 400 years. Hubble began observing the aftermath shortly after it was launched in 1990. The growing number of bright spots on the ring was produced by an onslaught of material unleashed by the supernova event. Image credit: NASA, ESA, and R. Kirshner (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation) and P. Challis (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) (CC BY 4.0)

Facts

SN 1987A was discovered by the Canadian astronomer Ian Shelton and telescope operator Oscar Duhalde at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile on February 24, 1987. Amateur astronomer Albert Jones discovered it independently from New Zealand on the same day.

Shelton reported the discovery of a magnitude 5 supernova that occurred 18 arcminutes west and 10 arcminutes south of the Tarantula Nebula (NGC 2070), one of the largest stellar nurseries in the Local Group. The astronomer discovered the supernova on a 3-hour exposure taken with a 0.25-m astrograph, after it had brightened by at least 8 magnitudes since the previous night. He suspected that it was associated with the open cluster NGC 2044. Duhalde spotted the supernova visually at Las Campanas on the same night.

Subsequent investigations of earlier photographs of the region showed that the supernova had brightened rapidly on February 23.

SN 1987A was the nearest observed supernova since Kepler’s Supernova (SN 1604), a type Ia supernova observed in the constellation Ophiuchus in 1604. Kepler’s Supernova occurred in our own Milky Way galaxy, less than 20,000 light years from Earth. With a peak magnitude of -2.5, it was visible during the day for several weeks. It was named after the German astronomer Johannes Kepler, who studied it extensively and wrote a book about it, called De Stella Nova.

Time-lapse animation of SN1987A from 1994 to 2009. Image credit: Mark McDonald; Source: Larsson, J. et al. (2011). “X-ray illumination of the ejecta of supernova 1987A”. Nature 474 (7352): 484–486. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

How to find Supernova 1987A

The Supernova 1987A occurred in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way. The dwarf galaxy lies approximately 163,000 light-years away and is about 32,200 light years across. It stretches across around 10 degrees of the southern sky. On a clear night, the galaxy is easily visible to the unaided eye as a detached piece of the Milky Way.

The Large Magellanic Cloud can be found by extending a line from Sirius in Canis Major through Canopus in Carina. The two brightest stars in the sky point in the general direction of the LMC. SN 1987A lies southwest of the bright, large Tarantula Nebula.

The best time of the year to observe the Large Magellanic Cloud and other deep sky objects in Dorado is during the month of January, when the constellation rises higher above the horizon in the early evening.

Location of the Large Magellanic Cloud, image: Stellarium

Location of the Supernova 1987A in the Large Magellanic Cloud, image: Stellarium

SN 1987A

| Constellation | Dorado |

| Object type | Supernova remnant |

| Event type | Type II supernova (peculiar) |

| Spectral type | SNIIpec |

| Date | February 24, 1987 |

| Host galaxy | Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) |

| Right ascension | 05h 35m 28.020s |

| Declination | −69° 16′ 11.07″ |

| Apparent magnitude (peak) | +2.9 |

| Apparent size | 0.03′ × 0.03′ |

| Distance | 168,000 light-years (51.4 kiloparsecs) |

| Progenitor | Sanduleak -69 202 |

| Names and designations | Supernova 1987A, SN 1987A, SNR 1987A, SNR J0535.5-6916, SK -69 202, INTREF 262, AAVSO 0534-69, SNR B0535-69.3, [BMD2010] CPD-69 402, LMC SN, UBV M 51417, GEN# +8.58690202, GSC 09162-00821, INTREF 262, SSTISAGE1C J053528.01-691611.0, HSO BMHERICC J083.8662-69.2699, SRGA J053525.0-691621, [HP99] 854, USNO-B1.0 0207-00125299, WISE J053527.97-691610.9, WISEA J053527.99-691610.9, [SHP2000] LMC 264, 2XMM J053528.1-691611, XMMU J053528.5-691614, MCSNR J0535-6916, [BMD2010] SNR J0535.5-6916, [GC2009] J053527.99-691611.1, [WS90] 1, [WLJ87] Star 1, [WS91b] Star 1, [WSI2008] 884 |

Images

This image shows the entire region around supernova 1987A. The most prominent feature in the image is a ring with dozens of bright spots. Credit: NASA, ESA, K. France (University of Colordo, Boulder), and P. Challis and R. Kirshner (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) (PD)

This NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 image shows the glowing gas ring around supernova 1987A, as seen on February 2, 2000. The gas, excited by light from the supernova event, has been fading for a decade, but parts of it are now being heated by the collision of an invisible shock wave. Image credit: NASA/ESA, Peter Challis and Robert Kirshner (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics), Peter Garnavich (University of Notre Dame) and the SINS collaboration (CC BY 4.0)

Photograph of the ring around Supernova 1987A (SN1987A) taken on December 7th, 2001 by the Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: NASA, P. Challis, R. Kirshner (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) and B. Sugerman (STScI) (PD)

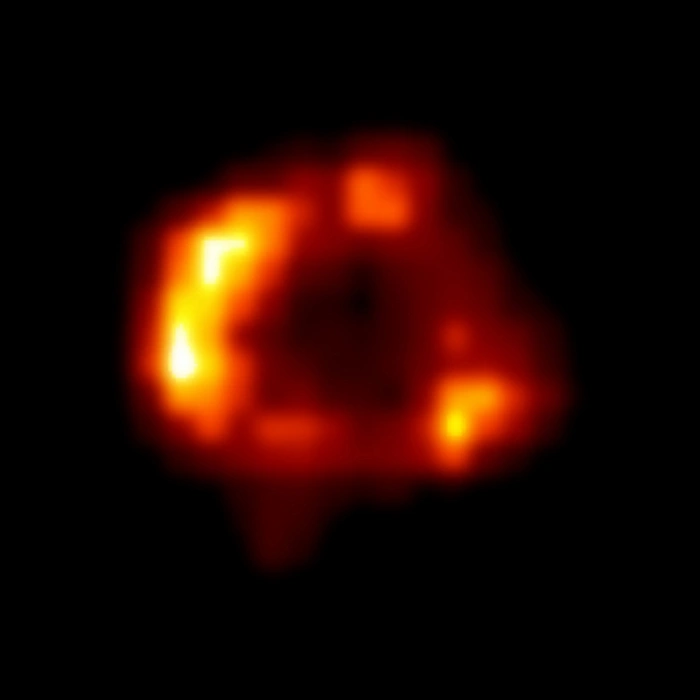

The Chandra X-ray image of SN 1987A made in January 2000 shows an expanding shell of hot gas produced by the supernova. This observation and an earlier Chandra observation in October 1999 are the earliest X-ray images ever made of a shock wave following a supernova event. The colors represent different intensities of X-ray emission, with white being the brightest. Recent optical observations of SN 1987A with the Hubble Space Telescope have revealed gradually brightening hot spots from a ring of matter that was ejected by the star thousands of years before it went out as a supernova. Chandra’s X-ray image shows the cause for this brightening ring. A shock wave, traveling at a speed of 4,500 kilometers per second (10 million miles per hour), is smashing into portions of the optical ring. The gas in the expanding shell has a temperature of about 10 million degrees Celsius, and is visible only with an X-ray telescope. Image credit: NASA/CXC/SAO/PSU/D.Burrows et al. (PD)

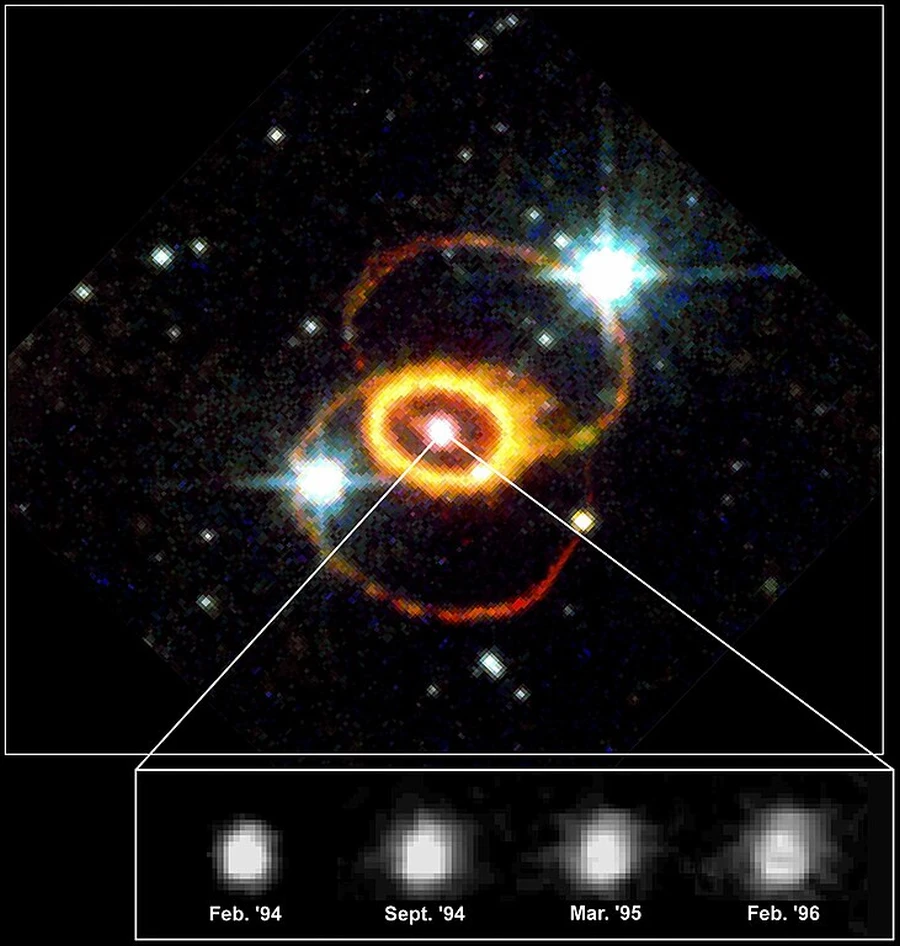

This Hubble Space Telescope picture shows Supernova 1987A and its neighborhood. The series of four panels shows the evolution of the SN 1987A debris from February 1994 to February 1996. Material from the stellar interior was ejected into space during the supernova event in February 1987. The debris is expanding at nearly 6 million miles per hour (about 2680 kilometres per second). Credit: Chun Shing Jason Pun (NASA/ESA/GSFC), Robert P. Kirshner (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics), and NASA/ESA (PD)

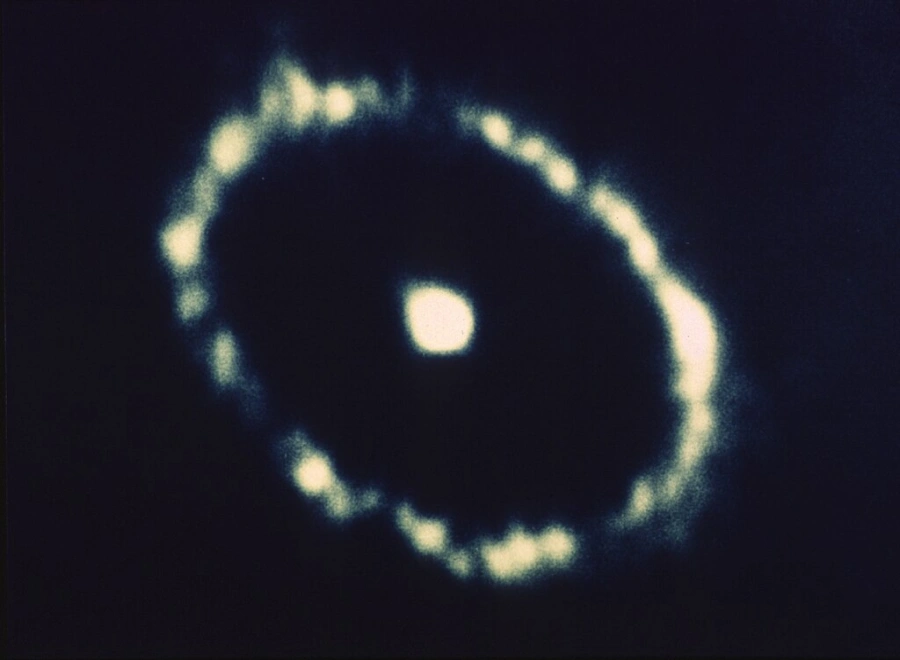

A NASA Hubble Space Telescope image of a gaseous ring surrounding the supernova 1987A, which occurred on February 23, 1987 in the Large Magellanic Cloud, an irregular satellite galaxy of the Milky Way. In this image, taken with the European Space Agency’s Faint Object Camera (FOC), HST’s 0.07 are second resolution reveals clumpy structure in the ring which indicates that the material is not uniformly distributed. The ring is a relic that was ejected by the progenitor star several thousand years before the supernova event. The ring is a real equatorial structure in the fossil stellar envelope. The ring glows because it was heated to more than 20,000 degrees by radiation from the supernova. Because the ring is inclined approximately 43 degrees along the line-of-sight, light emitted from the far edge of the ring arrived at Earth nearly one year after light arrived from the forward edge of ring. This delay time allows for an accurate estimate of the ring’s physical diameter, which 1.37 light- years. (This estimate is based upon a detailed analysis of data collected over a three year period by NASA/ESA’s International Ultraviolet Explorer satellite). By comparing the ring’s physical diameter with the ring’s angular diameter of 1.66 arc seconds – as measured quite accurately from the FOC image – astronomers have calculated the distance to the Large Magellanic Cloud with unprecedented accuracy, of 169,000 light-years (to within 5%). This false-color image was obtained in the light of doubly ionized oxygen, and then computer reconstructed to bring out additional detail. Credit: NASA and ESA (PD)

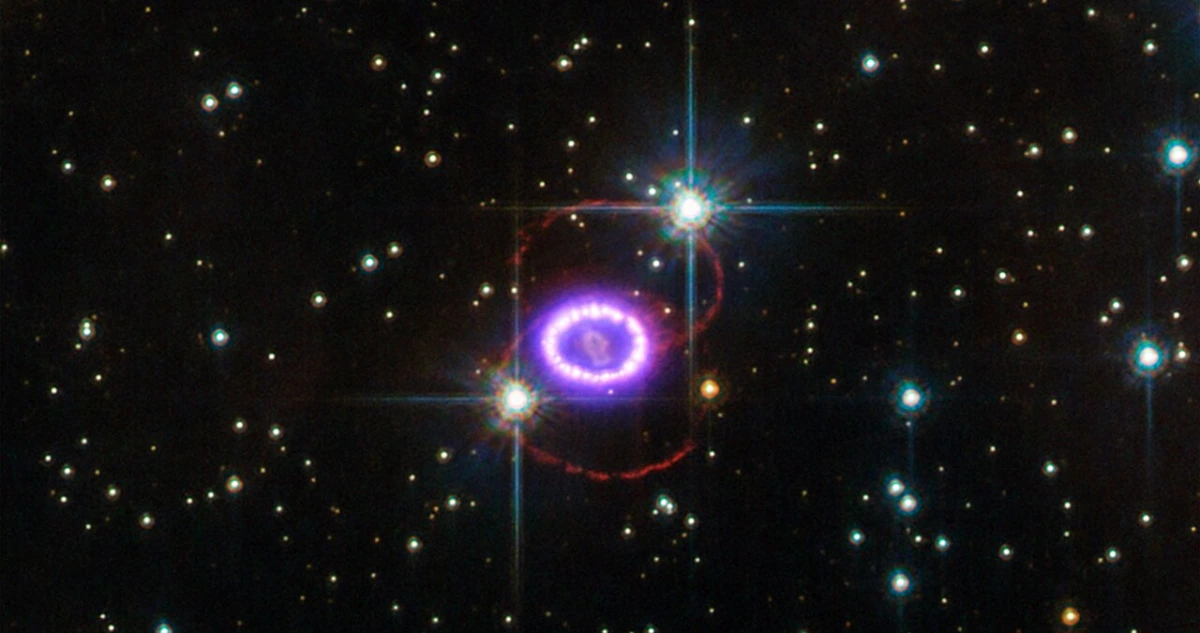

This new image of the supernova remnant SN 1987A was taken by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope in January 2017 using its Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3). Since its launch in 1990 Hubble has observed the expanding dust cloud of SN 1987A several times and this way helped astronomers to create a better understanding of these cosmic events. Supernova 1987A is located in the centre of the image amidst a backdrop of stars. The bright ring around the central region of the progenitor star is composed of material ejected by the star about 20 000 years before the actual supernova took place. The supernova is surrounded by gaseous clouds. The clouds’ red colour represents the glow of hydrogen gas. The colours of the foreground and background stars were added from observations taken by Hubble’s Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2). Image: NASA, ESA, and R. Kirshner (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation) and P. Challis (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) (CC BY 4.0)