R136 is the central concentration of stars in the open cluster NGC 2070, which lies at the centre of the Tarantula Nebula. Packed into a region only a few light-years across, the young cluster contains some of the most massive and luminous stars known, each blazing with the power of millions of Suns. The dense swarm of stars challenges our understanding of how stars form, how massive they can become, and how turbulent environments shape the evolution of active stellar nurseries and their surroundings.

The R136 cluster is the primary source of the ionization that makes the Tarantula Nebula visible. It is one of the most energetic open clusters known. Its brightest stars shine at magnitudes 12 – 14. With intrinsic luminosities over a million times that of our Sun, these stars generate more energy within a matter of seconds than the Sun does over the course of a whole year.

R136 includes 72 exceptionally luminous and massive stars packed within only 16 light years (5 parsecs) of the cluster’s centre. The region has an apparent size of 20 arcseconds. The stellar density of R136 is about 200 times that of an average OB association.

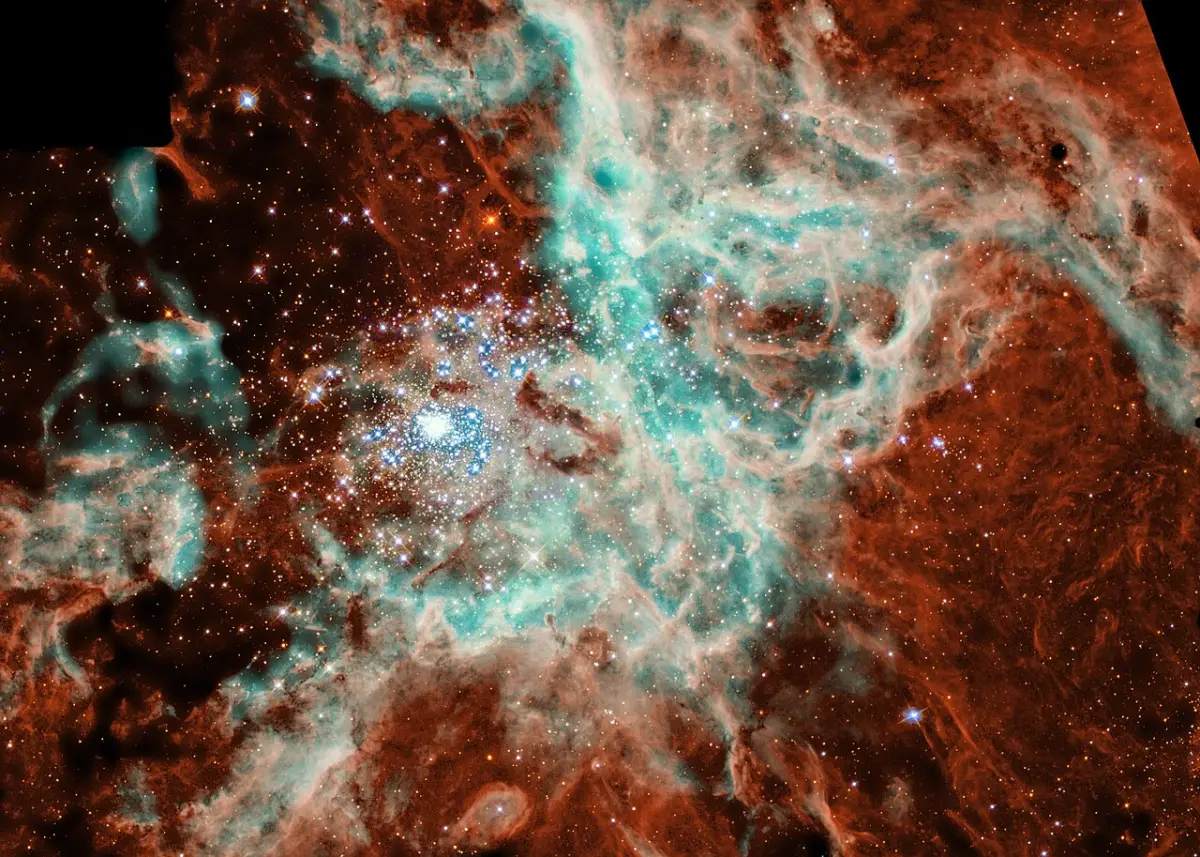

The Hubble Space Telescope captured this image of the massive young stellar grouping R136. The cluster of stars resides in the 30 Doradus nebula, a turbulent star birth region in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), a satellite galaxy of our Milky Way. The blue color is light from the hottest, most massive stars; the green from the glow of oxygen; and the red from fluorescing hydrogen. Image credit: NASA, ESA, Elena Sabbi (ESA, STScI) ACKNOWLEDGMENT: Robert O’Connell (UVA), SOC-WFC3 (PD)

The brightest members of R136 are Wolf-Rayet stars and massive O-type stars. The most prominent member, the Wolf-Rayet star R136a1, is currently the most massive and luminous star known. Its neighbours R136a2 and R136a3 are not too far behind.

However, R136 is much more than a collection of record-breaking stars. Hubble observations of the cluster have led astronomers to rewrite the old models of star formation, which largely focused on the formation of massive stars in isolation. Many of the insights gained by studying the massive cluster members were later integrated into broader galaxy evolution models.

Additionally, R136 serves as a nearby analogue for the conditions in the starburst regions of the early universe. The cluster has helped astronomers understand how the first generation of stars could reach very high masses. In effect, R136 is used as a bridge that connects the local universe with cosmological theory.

The cluster has a mass of 90,000 solar masses. Earlier estimates gave it a mass of 450,000 solar masses. With such a high mass, the young cluster would eventually evolve into a globular cluster.

The stars of R136 are still very young. The cluster has an estimated age of less than 2 million years. Astronomers have not found evidence that any members had already gone out as supernovae. They have also not detected any blue hypergiants, red supergiants, or luminous blue variables in the cluster. Even though they will not live very long lives, most cluster members are not yet at a highly evolved stage of their evolutionary cycle.

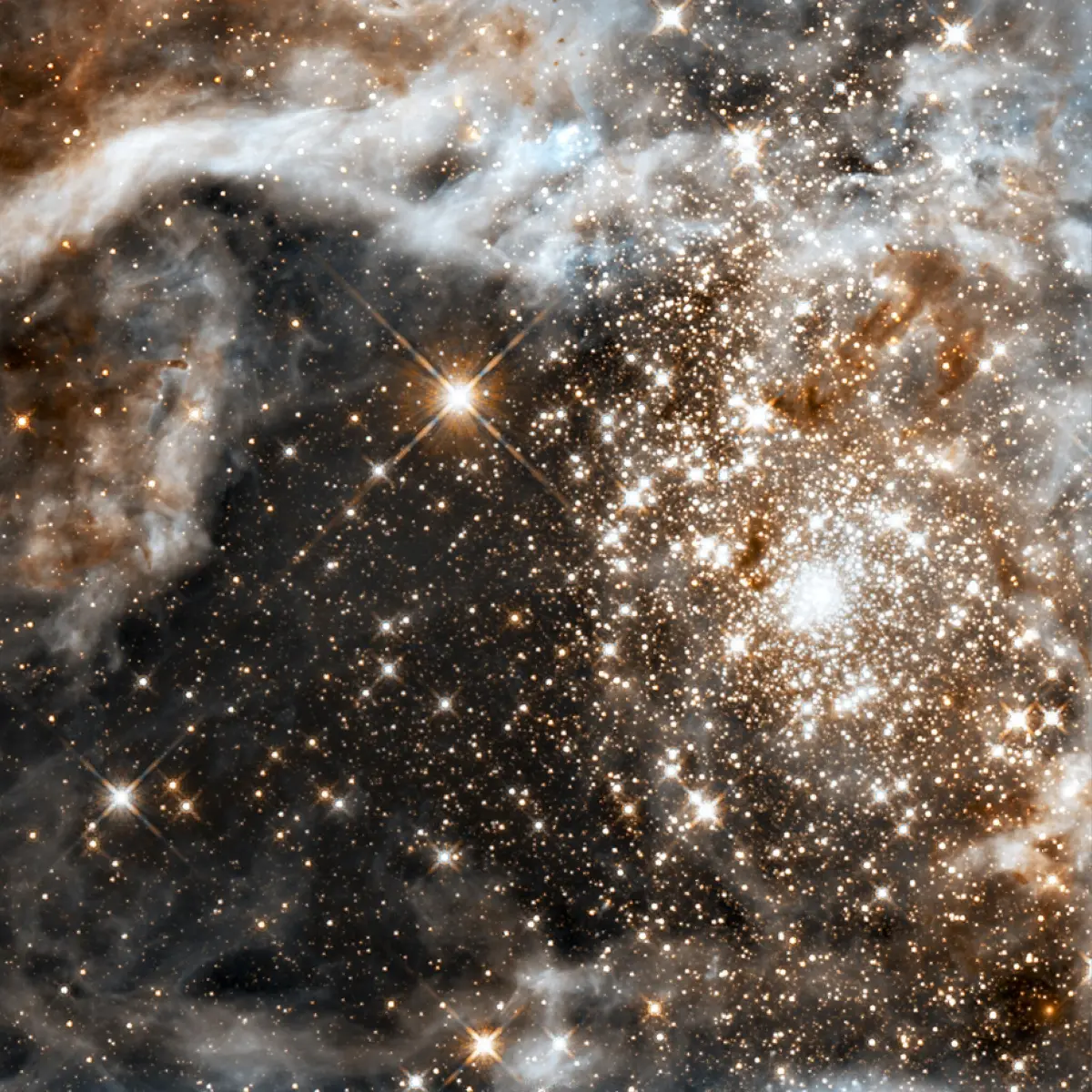

The massive, young stellar grouping, called R136, is only a few million years old and resides in the 30 Doradus Nebula. Many of the stars are among the most massive known. Several of them are over 100 times more massive than our Sun. These hefty stars are destined to become supernovae in a few million years. This image, taken by Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3, spans about 100 light-years. The nebula is close enough to Earth that Hubble can resolve individual stars, giving astronomers important information about the stars’ birth and evolution. It was taken at infrared wavelengths (1.1 microns and 1.6 microns). Hubble sees through the dusty nebula, revealing many stars that cannot be seen in visible light. The large bright star just above the center of the image is in the 30 Doradus nebula. Image: NASA, ESA, F. Paresce (INAF-IASF, Bologna, Italy), R. O’Connell (University of Virginia, Charlottesville), and the Wide Field Camera 3 Science Oversight Committee (PD)

Home to stellar giants

R136 contains some of the most massive stars discovered to date, including R136a1, R136a2, R136a3, and R136c. The high concentration of these young, luminous stars qualifies R136 as a starburst region.

The brightest stars of R136 are Wolf-Rayet stars (WNh), hot blue O-type supergiants, and OIf/WN slash stars with intermediate spectral features. All these stars are immensely massive and luminous.

More modest members cannot be resolved among their hot neighbours at such a large distance. However, astronomers have been able to detect a smaller number of B-type stars that were still on the main sequence. These stars are located on the outskirts of R136.

The brightest and most massive members of the cluster include the WN stars R136a1, R136a2, R136a3, and R136c, and the hot blue supergiants R136a5, R136a6 and R136b.

R136 stars

| Name | Spectral class | Mass (M☉) | Temperature (K) | Luminosity (L☉) |

| R136a1 | WN5h | 291 ± 46 | 46,000 | 7,244,000 |

| R136a2 | WN5h | 195 ± 35 | 47,000 | 5,129,000 |

| R136a3 | WN5h | 184 ± 40 | 50,000 | 5,012,000 |

| R136a4 | O3 V((f*))(n) | 108 | 50,000 | 1,905,000 |

| R136a5 | O2I(n)f* | 116 | 48,000 | 2,089,000 |

| R136a6 | O2I(n)f*p | 105 | 52,000 | 1,738,000 |

| R136a7 | O3III(f*) | 127 | 54,000 | 2,291,000 |

| R136a8 | O2–3V | 96 | 49,500 | 1,479,000 |

| R136b | O4If | 92 | 35,500 | 2,239,000 |

| R136c | WN5h | 142 | 42,170 | 3,802,000 |

R136a1 is currently the most massive and luminous star known. It has an estimated mass of around 291 solar masses and shines with 7,244,000 solar luminosities. The star is only 1 million years old.

A previous record-holder, the Wolf-Rayet star BAT99-98, lies in the larger NGC 2070, near R136. It has a similar mass and luminosity to the brightest members of R136. The star is believed to have had an initial mass of 250 solar masses and has shed around 20 solar masses of material through a strong stellar wind. BAT99-98 has an estimated luminosity of 5.012 million Suns, rivalling R136a2 and R136a3 in energy output.

This near-infrared image obtained with GeMS adaptive optics system resolves the stars inside RMC 136, a giant star cluster within the Tarantula Nebula in the Large Magellanic Cloud. The cluster produces most of the energy that energizes the Tarantula Nebula. The estimated mass of the cluster is about half a million times the mass of the sun, suggesting it will probably become a globular cluster in the future. Image credit: International Gemini Observatory, Robert Blum (National Optical Astronomy Observatory) and T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage) (CC BY 4.0)

Runaway stars

Some members of R136 have already escaped the cluster’s pull. Astronomers suspect that the massive Wolf-Rayet star VFTS 682 may have been ejected from the cluster. With a mass of 137.8 solar masses, it is unlikely that the star formed in isolation.

The runaway star currently lies more than 95 light years northeast of R136 in the larger Tarantula region. With a luminosity of 3,200,000 million Suns, VFTS 682 is one of the most luminous stars known.

In 2024, a team led by Mitchel Stoop, University of Amsterdam, identified 55 massive runaway stars that were dynamically ejected from R136. These young stars have masses in the range from 5 to 140 solar masses and are moving in different directions from the home cluster. They have travelled distances of 3 to 460 parsecs (9.78 – 1,500 ly) from R136.

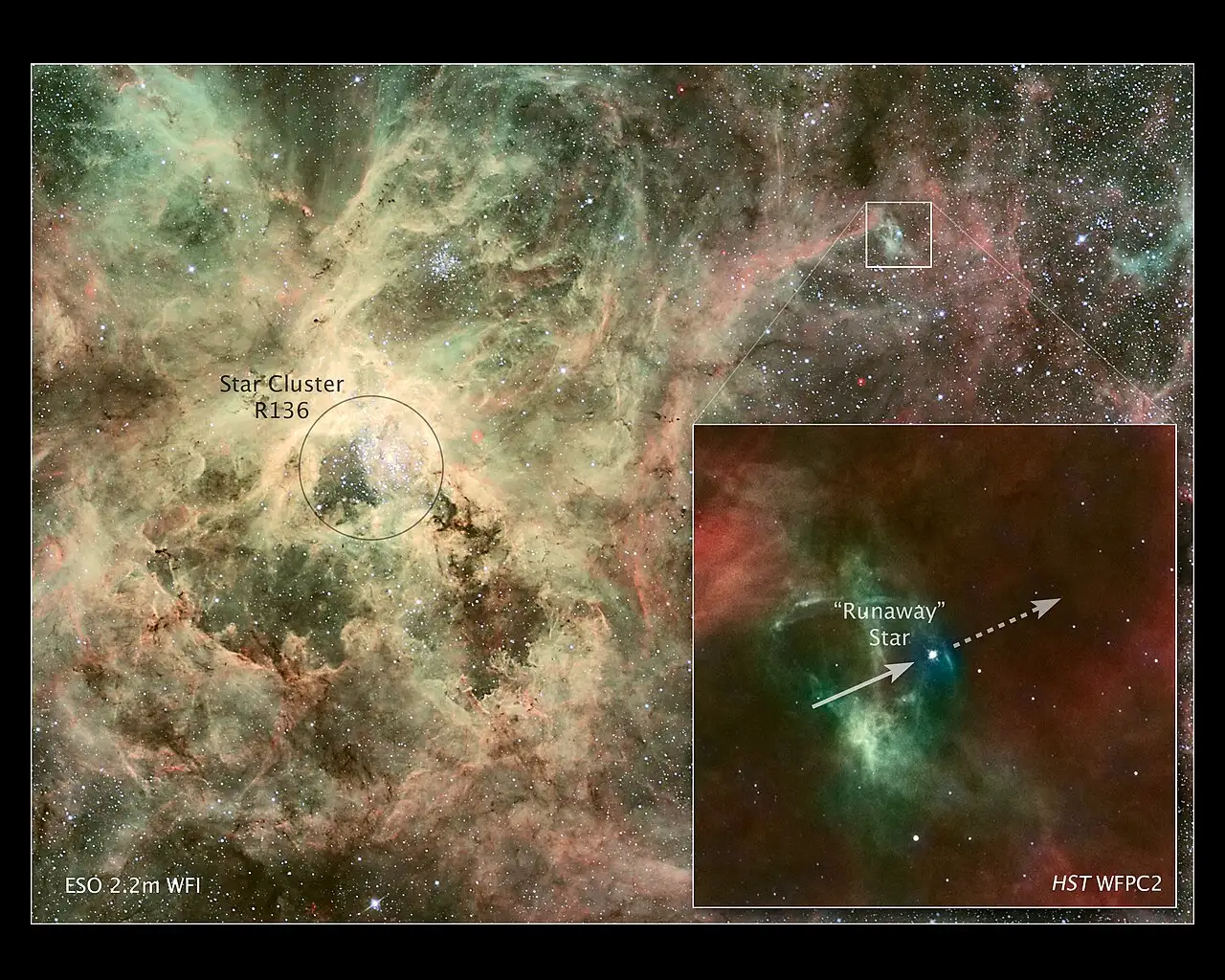

This view shows part of the very active star-forming region around the Tarantula Nebula in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a small neighbour of the Milky Way. At the upper left is the brilliant but isolated star VFTS 682 and at the lower right is the very rich star cluster R 136. The origins of VFTS 682 are unclear — was it ejected from R 136 or did it form on its own? The star appears yellow-red in this view, which includes both visible-light and infrared images from the Wide Field Imager at the 2.2-metre MPG/ESO telescope at La Silla and the 4.1-metre infrared VISTA telescope at Paranal, because of the effects of dust. Image credit: ESO/M.-R. Cioni/VISTA Magellanic Cloud survey. Acknowledgment: Cambridge Astronomical Survey Unit (CC BY 4.0)

The researchers found that R136 has launched up to a third of its most massive members within the last few million years. These runaways move at speeds of over 100,000 km/h.

The team concluded that the stars were expelled from the cluster during two periods. One was around 1.8 million years ago, when the cluster formed. These ejected stars are moving at high velocities in different directions. The other episode occurred 200,000 years ago and the stars that were launched are travelling more slowly in a preferred direction.

The astronomers proposed that the second episode may have been caused by the interaction of R136 with a nearby cluster. The two clusters may eventually merge.

This image of the 30 Doradus Nebula, a rambunctious stellar nursery, and the enlarged inset photo show a heavyweight star that may have been kicked out of its home by a pair of heftier siblings. In the inset image at right, an arrow points to the stellar runaway and a dashed arrow to its presumed direction of motion. The image was taken by the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2) aboard the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. The heavyweight star, called 30 Dor #016, is 90 times more massive than the Sun and is travelling at more than 400 000 kilometres an hour from its home. Credit: NASA, ESA, J. Walsh (ST-ECF); Acknowledgment: Z. Levay (STScI); Credit for ESO image: ESO; Acknowledgments: J. Alves (Calar Alto, Spain), B. Vandame, and Y. Beletski (ESO); Processing by B. Fosbury (ST-ECF) (CC BY 3.0)

Facts

Unlike R136, which was not resolved until the 1980s and 1990s, the larger NGC 2070 is visible in binoculars and small telescopes. The candidate super star cluster is listed as Caldwell 103 (C103) in the Caldwell catalogue of objects visible in amateur telescopes. It has an apparent visual magnitude of 7.25 and an angular size of 3.5 by 3.5 arcminutes.

The cluster R136 does not have a proper name. The designation R136 (or RMC 136) comes from the census of optically bright stars in the Radcliffe Observatory Magellanic Clouds catalogue, compiled by Feast, Thackeray and Wesseling in 1960. The cluster was listed as a stellar object in the RMC catalogue.

In 1980, Feitzinger et al. resolved the three main visual components – R136a, R136b, and R136c – at the La Silla Observatory in Chile.

R136a was shown to be a multiple system by Weigelt and Baier in 1985. The astronomers used speckle interferometry and identified eight components located within 1 arcsecond of the cluster’s core.

Before R136a was resolved, some astronomers believed that it was a single star about 3,000 times the mass of the Sun. At the time, a single exceptionally massive star seemed more conceivable that several high-mass stars packed within half a parsec (1.63 ly).

The James Webb Space Telescope reveals details of the structure and composition of the Tarantula Nebula, as well as dozens of background galaxies. Stellar nursery 30 Doradus gets its nickname of the Tarantula Nebula from its long, dusty filaments. Located in the Large Magellanic Cloud galaxy, it’s the largest and brightest star-forming region near our own galaxy, plus home to the hottest, most massive stars known. The center of this image, taken by Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera instrument (NIRCam), has been hollowed out by the radiation from young, massive stars (seen in sparkling pale blue). Only the densest surrounding areas of the nebula resist erosion, forming the pillars that appear to point back towards the cluster of stars in the center. The pillars are home to still-forming stars, which will eventually leave their dusty cocoons and help shape the nebula. Image: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Webb ERO Production Team (PD)

R136 and the upper limits of star formation

The young star cluster was initially catalogued as an unresolved stellar object with the designation HD 38268 in the Henry Draper catalogue and as the Wolf-Rayet star Brey 82.

By 1984, astronomers had begun to suspect that R136a was a cluster. A team of researchers at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) in Chile and Washburn University, Wisconsin, combined optical and ultraviolet (UV) data to study the luminous object. They concluded that it was either a single star with a mass of 750 solar masses or a cluster of six to 20 massive stars with the spectral type O3.

With the arrival of Hubble in the 1990s, astronomers were able to resolve more individual stars. The space telescope resolved R136a into at least 12 stars and found over 200 massive, luminous new members of R136.

In 2010, a team led by Paul A. Crowther, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Sheffield, UK, found that the members of R136 had initial masses in the range between 160 and 320 solar masses. The findings were based on spectroscopic data obtained with the Very Large Telescope (VLT) and the Hubble Space Telescope (HST).

This challenged the upper limit on stellar mass, which was 150 solar masses at the time. Less than two decades ago, astronomers believed that radiation pressure from a forming massive star halted further accretion of material. In other words, the accepted evolutionary models effectively capped the star’s growth.

High-resolution observations with Hubble and other telescopes showed direct evidence that these models were wrong. At this point, theorists began to explore stellar evolution models that allowed for much higher stellar masses under the right conditions.

A Hubble Space Telescope image of the R136 super star cluster, near the center of the 30 Doradus Nebula, also known as the Tarantula Nebula or NGC 2070. Image: NASA, ESA, F. Paresce (INAF-IASF, Bologna, Italy), R. O’Connell (University of Virginia, Charlottesville), and the Wide Field Camera 3 Science Oversight Committee (PD)

The discovery of R136a1 and its neighbours showed that very massive stars could indeed form in exceptionally dense clusters, where they were affected by gravitational interaction with other stars. These stars can grow faster because of the higher gas densities in the cluster centres, which result in higher accretion rates. The stars in the centre grow much larger because they accrete more material. The mechanism is known as competitive accretion.

In 2016, Crowther et al. observed R136 with the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) aboard Hubble and classified the brightest members of R136a. They identified three Wolf-Rayet stars (WN5), two O-type supergiants, and three O-type main sequence stars. The astronomers estimated an age of 1.5 million years for the cluster.

The evolution and fate of the most luminous members of R136 are still an uncertainty. In 2025, a study led by Z. Keszthelyi of the Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy, University of Amsterdam, used stellar evolution models to gain insights into the evolutionary history of R136a1, R136a2, and R136a3. The international team of astronomers proposed that the stars would not end their lives as pair-instability supernovae and that they would not produce gamma-ray bursts.

The researchers found that the star with the highest initial mass has the highest mass-loss rates, leading to a decline in luminosity. Based on the lower helium abundance, they suggested that R136a1 may have initially been less massive than R136a2 and R136a3. They estimated initial masses of 346 ± 42 M⊙ for R136a1 and at least 500 M⊙ for R136a2 and R136a3.

This Hubble image shows a cosmic creepy-crawly known as the Tarantula Nebula in infrared light. This region is full of star clusters, glowing gas, and thick dark dust. Created using observations taken as part of the Hubble Tarantula Treasury Project (HTTP), this image was snapped using Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) and Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS). The Hubble Tarantula Treasury Project (HTTP) is scanning and imaging many of the many millions of stars within the Tarantula, mapping out the locations and properties of the nebula’s stellar inhabitants. These observations will help astronomers to piece together an understanding of the nebula’s skeleton, viewing its starry structure. Image credit: NASA, ESA, E. Sabbi (STScI) (CC BY 3.0)

A powerhouse in the Tarantula Nebula

R136 comprises the central portion of the larger star cluster NGC 2070, which lies at the heart of the Tarantula Nebula (30 Doradus). The cosmic Tarantula is a large star-forming region located in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way. It is one of the largest H II regions in the Local Group of galaxies, along with NGC 604 in the Triangulum Galaxy. Stretching 1,860 light-years across, it is the most active starburst region in the Local Group. It is located 160,000 light-years from the solar system.

Even though it lies in another galaxy, the Tarantula Nebula can be observed in small telescopes. It has an angular size of 40 by 25 arcminutes and an apparent visual magnitude of 8. If it were as close to us as the Orion Nebula (1,344 light-years), the giant stellar nursery would cast shadows.

At declination -69°, the Tarantula Nebula never rises above the horizon for observers north of the latitude 21° N. The best time of the year to observe the nebula and other deep sky objects in the Large Magellanic Cloud is during the month of January.

This composite image shows the star-forming region 30 Doradus, also known as the Tarantula Nebula. The background image, taken in the infrared, is itself a composite: it was captured by the HAWK-I instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) and the Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy (VISTA), shows bright stars and light, pinkish clouds of hot gas. The bright red-yellow streaks that have been superimposed on the image come from radio observations taken by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), revealing regions of cold, dense gas which have the potential to collapse and form stars. The unique web-like structure of the gas clouds led astronomers to the nebula’s spidery nickname. Image credit: ESO, ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/Wong et al., ESO/M.-R. Cioni/VISTA Magellanic Cloud survey. Acknowledgment: Cambridge Astronomical Survey Unit (CC BY 4.0)

R136

| Constellation | Dorado |

| Object type | Open cluster |

| Right ascension | 05h 38m 42.396s |

| Declination | −69° 06′ 03.36″ |

| Apparent magnitude | 9.50 |

| Distance | 157,000 light-years (48,500 parsecs) |

| Mass | 90,000 M☉ |

| Age | 1.5 million years (0.8 – 1.8 Myr) |

| Names and designations | R136, RMC 136, Radcliffe 136, Brey 82, CAL 72, Dor IRS 99, 2E 1513, 2E 0539.1-6906, 1ES 0538-69.1B, [SHP2000] LMC 301, HD 38268, SAO 249329, SK -69 243, CPD-69 456, CD-69 324, LH 100, MH 15, HTR 15, WHHW 0539.1-6908, SKY# 9173, CSI-69 456 41, FD 66, GC 7114, GCRV 56615, PPM 354885, [NO95] 10, TYC 9163-1014-1, GEN# +1.00038268, GSC 09163-01014, UCAC2 1803442, JP11 1249, CCDM J05387-6906ABCD, IDS 05394-6909 ABCD |

The NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope has snapped a panoramic portrait of a vast, sculpted landscape of gas and dust where thousands of stars are being born. This fertile star-forming region, called the 30 Doradus Nebula, has a sparkling stellar centerpiece: the most spectacular cluster of massive stars in our cosmic neighborhood of about 25 galaxies. The mosaic picture shows that ultraviolet radiation and high-speed material unleashed by the stars in the cluster, called R136 [the large blue blob left of center], are weaving a tapestry of creation and destruction, triggering the collapse of looming gas and dust clouds and forming pillar-like structures that are incubators for nascent stars. Image: NASA/ESA, N. Walborn and J. Mamz-Apellaniz ( Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, MD), R. Barba (La Plata Observatory, La Plata, Argentina) (CC BY 4.0)